I’ll be the first to admit, there are times when the way our tax codes play out seems more like magic than accounting – especially when integrating your personal and corporate taxes. “Look, nothing up my sleeves,” says your tax professional. Can you believe it? That’s what this series is for: Putting some of the acts into slow-mo, so you can see the sleight of hand for yourself.

Today, we’ll talk about the magical dividend refund, whose purpose is to ensure that corporate shareholders don’t end up being unfairly taxed twice on the same income. Ready to see how this nifty trick works?

In my last blog post, I showed how Canadian interest income is taxed within a corporation. In our example, an Ontario-based corporation was taxed 50.17%, or $5,017 on $10,000 of Canadian interest income. This left $4,983 of after-tax income to reinvest in the corporation’s passive portfolio or to distribute to shareholders.

Let’s say this money were distributed to you, a shareholder and Ontario taxpayer. If there were no further adjustments, you’d then incur an additional $2,258 of personal taxes on the non-eligible dividend. (Trust me on that figure, and I’ll spare you the details so we can get to the good stuff.)

If you’re keeping an eye on the action, you can see how unfair this would be. Your combined corporate and personal taxes would be $7,275, for an effective tax rate of 72.75%. That’s considerably higher than Ontario’s top personal tax rate of 53.53%.

A Part 1 corporate tax disappearing act

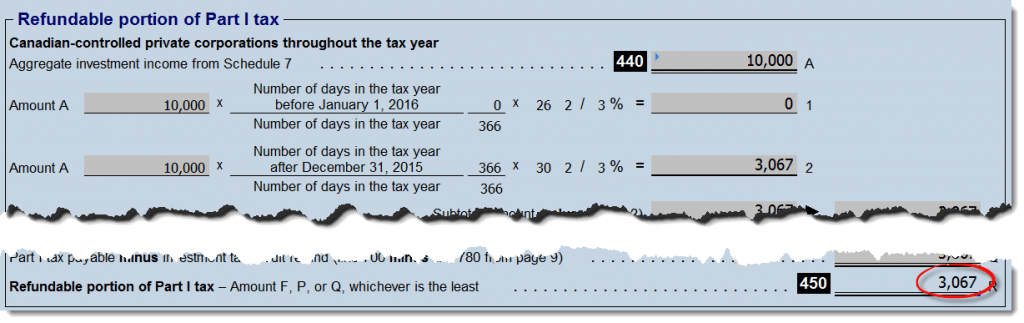

The government is well aware of this inconsistency, so they rightfully allow your corporation to “disappear” a portion of your otherwise unequal burden by obtaining a dividend refund when taxable dividends are paid out to shareholders. Specifically, we apply a bit of pixie dust to the federal 38.67% Part I tax payable on investment income to position your corporation to qualify for a refund on 30.67% of the aggregate investment income from Schedule 7. In our example, that’s $10,000 × 30.67% = $3,067.

The remaining 8% of the 38.67% federal Part I tax is non-refundable, as are provincial and territorial taxes like Ontario’s 11.5% tax.

Source: Corporate Taxprep – T2 Corporation Income Tax Return (2016)

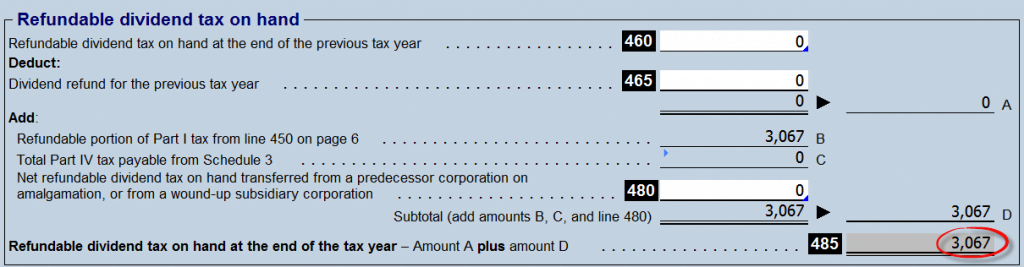

Refundable dividend tax on hand (RDTOH)

We’re not yet done with the fancy footwork. There’s also the ever-so-catchy refundable dividend tax on hand (RDTOH) account, where the available dividend refund described above accumulates.

To obtain the full dividend refund available, the corporation must pay out a taxable dividend of sufficient size to shareholders. The corporation is refunded 38.33% of each dollar of taxable dividends it distributes to shareholders. So in our example, a business owner would need to pay out taxable dividends of at least $8,002 to reclaim the full $3,067 of refundable taxes available in the RDTOH account balance ($3,067 ÷ 38.33%). This refunded amount of taxes is the actual dividend refund.

Source: Corporate Taxprep – T2 Corporation Income Tax Return (2016)

The Dividend Refund

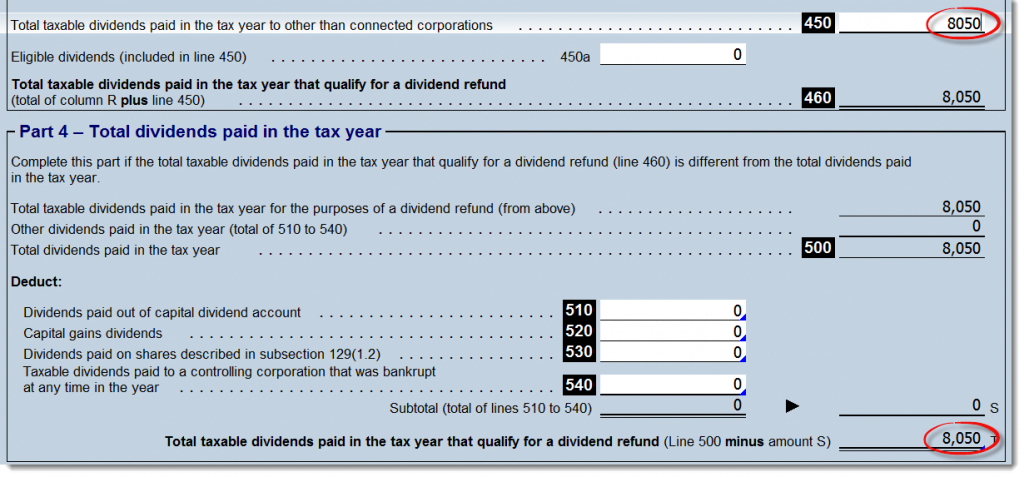

As mentioned in the discussion above, the corporation will have $8,050 available to distribute to its shareholders (once you include the dividend refund of $3,067 and the after-tax corporate income of $4,983). As this amount is higher than the required $8,002, we’ll have no issues receiving the full dividend refund.

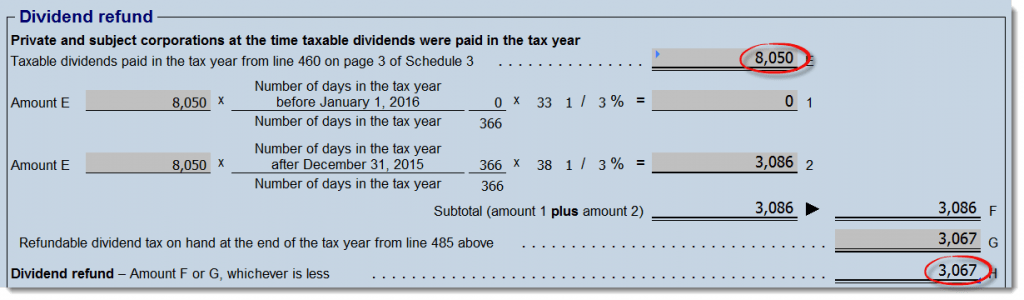

To pay out the taxable dividends to shareholders, the business owner would include $8,050 of taxable dividends on Schedule 3 (line 450). This figure would feed through to the dividend refund section of the corporate tax return, resulting in a dividend refund of $3,067.

If you’re watching closely, you may notice that the $8,050 dividend payment should generate a dividend refund of $3,086 ($8,050 × 38.33%). But only $3,067 is actually refunded, since this is the balance available in the RDTOH account.

Source: Corporate Taxprep – Schedule 3 (2016)

Source: Corporate Taxprep – T2 Corporation Income Tax Return (2016)

Did you follow all that? Below is the summary.

Next week, we’ll look at how tax integration works (or doesn’t) with Canadian interest income. We’ll also look at whether it makes sense to retain the investment income within the corporation for reinvestment, or dividend it out to the shareholders.

The Dividend Refund

| General formula | Amount | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian interest income | $10,000 | |

| Deduct: Part I tax – non-refundable | ($800) | $10,000 × 8% |

| Deduct: Part I tax - refundable | ($3,067) | $10,000 × 30.67% |

| Deduct: Provincial or territorial tax – non-refundable | ($1,150) | $10,000 × 11.5% (Ontario) |

| Equals: After-tax corporate income | $4,983 | $10,000 - $800 - $3,067 - $1,150 |

| Add: Dividend refund | ($3,067) | $10,000 × 30.67% |

| Equals: Amount available to distribute as a taxable dividend | $8,050 | $4,983 + $3,067 |

Thanks for the article! Magical dividend refund seems useful.

Just want to add the reason why Dividend refund is calculated as 38.333% x Dividend paid. This is different from the Refundable portion of Part 1 tax calculated as 30.666% x Aggregate Income. The reason lies in the components included in Dividend refund (p6 of T2), which includes both Part 1 tax and Part 4 tax. Part 4 tax (Sch 3) is calculated as 38.333% x Dividends received by CCPC.

So the Dividend refund calculation has to be based on 38.333% otherwise Part 4 tax could not be 100% refunded if 30.666% is applied. On the other hand, Dividend refund is the whichever is less between RDTOH and 38.333% of Dividend paid. This ensures that there is no over-refund resulting from Part 1 tax scenario (RDTOH calculated based on 30.666% vs Dividend refund calculated based on 38.333%)

Hi

Assume

a) a CCPC (Holdco) has passive investments which include eligible dividends.

b) the CCPC distributes a dividend to a shareholder comprised of both the eligible dividends and other interest income

Does the portion that originated from “eligible dividends” remain characterized as “eligible” on the shareholders tax return or are they now “non-eligible”?

Thanks

@john qas: At the bottom of page 45 of the government’s discussion paper, they mention that “dividend income from publicly-traded stocks would no longer be treated as eligible dividends, as is currently the case, but would be treated as non-eligible dividends.”

https://www.fin.gc.ca/activty/consult/tppc-pfsp-eng.pdf

“his plan actually does create a relatively fair playing field between corporate and personal investors.”

That would be correct if one would totally ignore that the personal investors most often have some sort of pension in addition to their investment income, whereas the corporate investors don’t have that benefit.

@Cristian: The proposed rules will likely hit the youngest corporate investors the hardest (their young salaried counterparts will likely not have significant private pensions either).

This information is very helpful Justin. Based on this article, am I correct to assume that dividend payments are more tax efficient and less costly than payroll (T4) withdrawals for corporation owners? Especially because payroll withdrawals also entail both employee and employer CPP contributions.

@Silva: This article does not discuss the tax integration between salary vs. dividends (a more relevant article can be found here: https://www.canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/corporate-taxation-tax-integration-of-active-business-income/ )

The assumption that dividends are better than salary because you avoid CPP contributions does not factor in that by paying into CPP, you are actually receiving an asset (i.e. future inflation adjusted income).

Thanks for walking us through this complex topic… looking forward to future illustrations regarding capital gain taxation within corporations, especially with respect to index ETF gains (or losses) that could be compatible with tax loss selling.

PS – I’ve learned that Finance Minister Morneau’s proposed changes could result in an effective 73% tax rate and now I think I see how that would be achieved! Hopefully enough small business owners will voice concern about the effect upon their financial future considering we don’t get a pension, paid holidays, maternity, EI, etc!

@Ian: You’re very welcome! There’s plenty more articles on the way (I just have to lay the foundation before we can start discussing specific ETFs or capital gain strategies).

As for the 73% tax rate, I alluded to it a bit at the beginning of this post (the 72.75% tax rate before the dividend refund). Morneau is planning to do away with this magical dividend refund, but as I’ll show in a future post, his plan actually does create a relatively fair playing field between corporate and personal investors.

Hi Justin,

Thanks for the post. However I take issue with your comment “his plan actually does create a relatively fair playing field between corporate and personal investors”.

I would like to give you some context from a physician’s point of view on Morneu’s proposed changes.

Take these considerations into effect if you look at how a Canadian physician manages a Professional Corporation (FYI I am a physician):

– Physician’s have NO benefits or pension. Our investments strategies are much riskier than a defined benefit pension plan.

– Physician’s take on an average debt load of >$150k to train, and are much older when they start to have earning potential. Most are done residency in their 30’s (some in their 40’s). They must then first pay off their debts and only then have a significant ability to invest and benefit from compounding interest etc. Most physician’s retire MUCH later than the average pensioner.

– Physician compensation has been negotiated and priced knowing the tax advantages of a professional corporation. So if they suddenly eliminate that advantage, it would be considered grossly “unfair” that our fees remain the same while our take home income goes down if PC’s are changed in the way Morneau wants to change them. This is not in keeping with the good faith involved in setting physician fee schedules.

– Most assets outside of cash and investments in Professional Corporations for physicians have ZERO intrinsic value. For example a physician cannot sell off hardly any of their business assets, unlike another small business like a brick and mortar general store, for example. Things such as patient lists, a physician’s (hard earned) reputation in the medical community, money spent on continuing medical education, money spent on licensing and professional institutions carry NO instrinsic value that can be “sold” at the end of their career. This is vastly different from many other forms of small business. Therefore, physicians must rely on investment income as there is rarely anything they can sell upon retirement.

Thanks again for your extremely informative blog. I would like to hear your thoughts on my comments.

Regards

@Brad: My comment was not intended to offend – it is merely a fact about the proposed taxation of personal vs. corporate passive investments.

Your points are definitely valid – if the government intends to keep physicians working in Canada, they could consider offering them other benefits to compensate for the proposed tax changes:

– Government defined benefit pension plans

– Debt forgiveness of their student loans

– Higher incomes

Thanks for the headache Justin! Lol.

Good explanation though.

@Wreckingball: Glad to hear I’m not the only one with a headache ;)