I received this question from a reader of the blog (it’s also a question I receive on the daily from DIY investors):

“The Vanguard AA ETFs are very appealing in their simplicity in regards to maintenance and range of options. However, I am mindful of the tax-efficiency issues regarding holding these in a taxable account due to the premium bond holdings. Would holding VBAL in a taxable account for the sake of ultimate management ease be “significantly” outweighed by the financial benefit of crafting a more tax-efficient DIY bundle of ETFs in just the taxable account (such as a combo of ZDB, VCN and XAW)?”

As the reader correctly notes, the tax-inefficiencies in Vanguard’s AA ETFs mainly lie with the underlying bonds (not with the equities) – at least in taxable accounts. You see, many of the bonds in fixed income ETFs are currently trading at what’s called a “premium” to their maturity value. This basically means you’ll overpay for the bonds when you purchase them (and get stuck with a capital loss when they mature at a lower value), but receive more interest along the way (this extra interest is meant to compensate you for the initial sticker shock). Problem is, interest is fully taxable as income, whereas the capital loss you realize on the bonds at maturity can only offset capital gains (where only 50% of the gain is taxable). This inconsistent taxation between capital gains and interest income can lead to some interesting after-tax results.

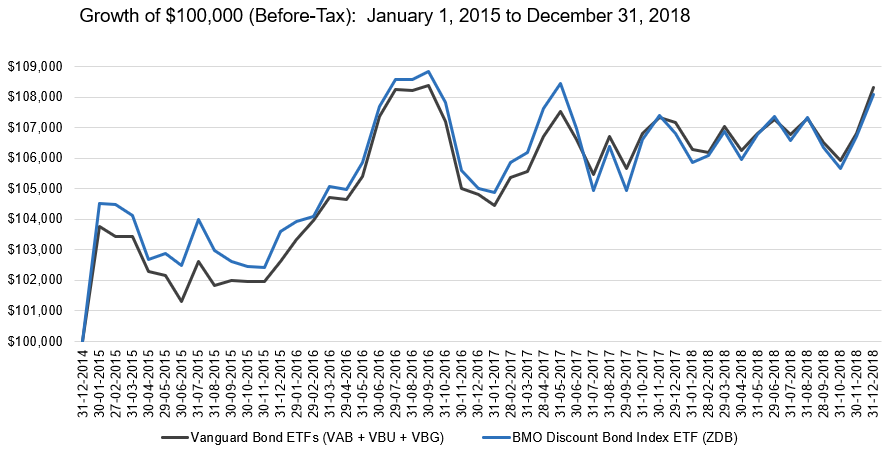

In the following analysis, we’re going to compare the actual before and after-tax returns of a relatively tax-efficient bond fund, the BMO Discount Bond Index ETF (ZDB) with the collection of Vanguard bond ETFs found in Vanguard’s asset allocation funds (with similar weightings):

• 58.8% Vanguard Canadian Aggregate Bond Index ETF (VAB)

• 18.6% Vanguard U.S. Aggregate Bond Index ETF (CAD-hedged) (VBU)

• 22.6% Vanguard Global ex-U.S. Aggregate Bond Index ETF (CAD-hedged) (VBG)

Each investment will start with $100,000 on January 1, 2015. Taxes on income will be paid when received (at the top Ontario tax rate) and any capital gains will be payable on December 31, 2018 (we have also assumed that any capital losses realized at that time can be used to offset existing capital gains). We’ll look at the before-tax returns first, then the after-tax returns, then throw some GICs into the mix for fun.

First Among Equals

Between 2015 and 2018, the $100,000 position in ZDB grew to $108,075, while the Vanguard bond ETFs grew to a similar value of $108,301. In percentage terms, ZDB returned 1.96% each year on average, while the Vanguard bond ETFs returned 2.01%. As the before-tax returns were nearly identical between the two investment options over the measurement period, this will make for an interesting after-tax comparison next.

Sources: BMO Global Asset Management, Vanguard Investments Canada Inc., cds.ca, taxtips.ca

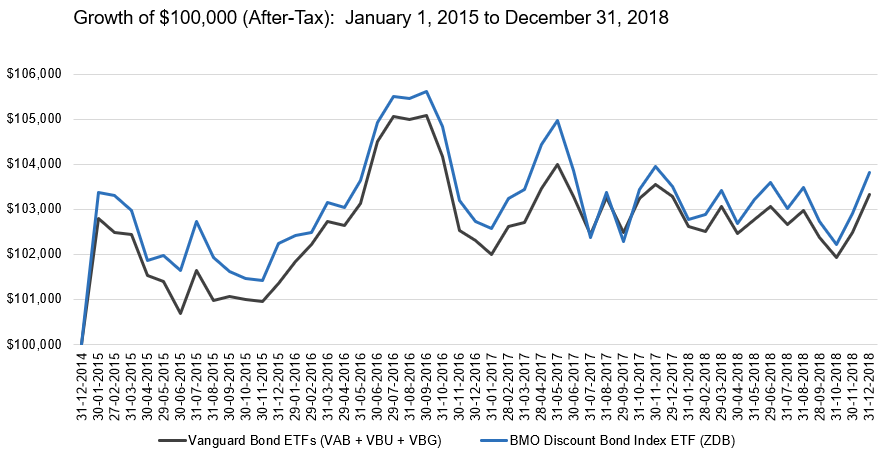

Tax Me If You Can

From an after-tax perspective (assuming the top rate for an Ontario taxpayer), the $100,000 position in ZDB grew to $103,821, while the Vanguard bond ETFs grew to only $103,333. In after-tax percentage terms, ZDB returned 0.94% each year on average, while the Vanguard bond ETFs returned 0.82% (for total after-tax outperformance of 0.12% per year).

Sources: BMO Global Asset Management, Vanguard Investments Canada Inc., cds.ca, taxtips.ca

Although 0.12% may seem trivial in the whole scheme of things (and it just might be), the Vanguard bond ETFs would have needed to earn an additional 0.25% per year before-tax if they had a chance of eking out another 0.12% per year after-tax [0.25% × (1 – 53.53% top Ontario tax rate)]. So, if 0.25% is the ballpark tax drag from these less efficient Vanguard bond ETFs, what does this translate into for taxable investors of the Vanguard asset allocation ETFs?

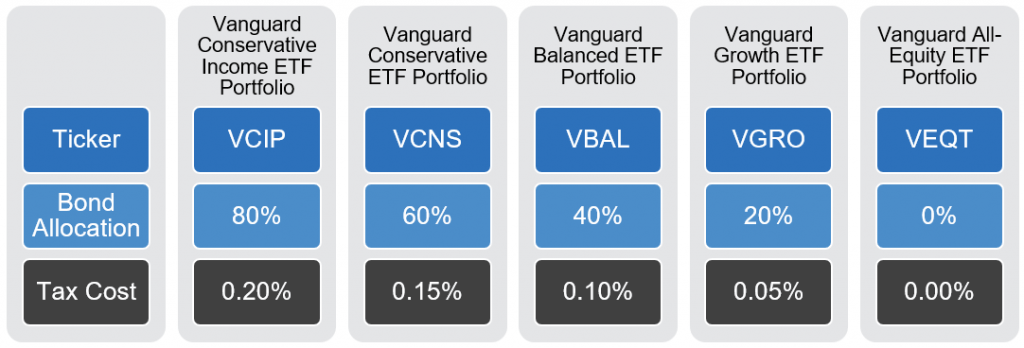

That depends on which ETF you’re invested in, as only the bond component has the potential for this specific “premium bond” tax cost. The more conservative your asset allocation, the greater the expected tax drag. For example, the estimated tax cost for the Vanguard Growth ETF Portfolio (VGRO), which allocates 20% to bonds, is only 0.05% (20% bond allocation × 0.25% tax cost), while the Vanguard Balanced ETF Portfolio (VBAL), which has a 40% allocation to bonds, is 0.10% (40% bond allocation × 0.25% tax cost). I’ve included a summary of the estimated additional tax cost for each Vanguard ETF in the image below.

Estimated Premium Bond Tax Cost in a Taxable Account

Sources: BMO Global Asset Management, Vanguard Investments Canada Inc., cds.ca, taxtips.ca

So, should you avoid these ETFs in taxable accounts entirely? I don’t think so, especially if they help you maintain discipline and stay invested. Managing more than one ETF requires slightly more effort, and trying to keep up to speed on all the tax jargon is exhausting (take my word for it). Potentially giving up 10 basis points of return for less time with family and friends doesn’t seem worth it to me, but I’ll let you decide for yourself. I’ve also outlined another fixed income alternative below.

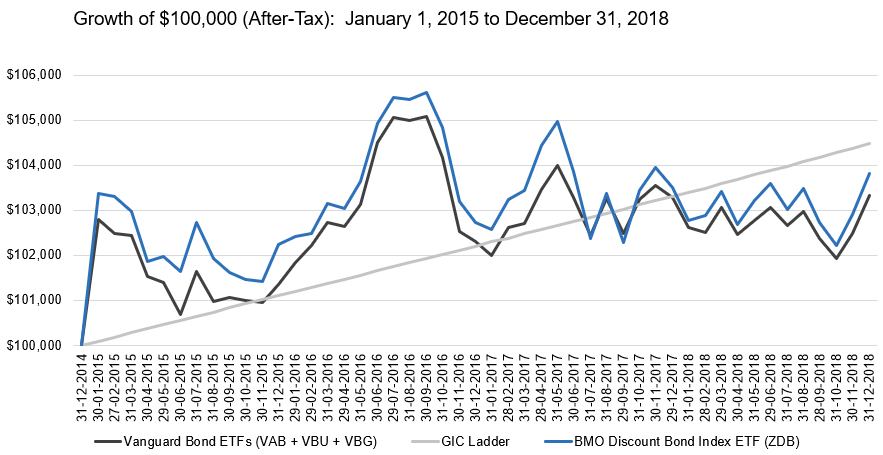

Climbing the GIC ladder

If the exhilarating highs and depressing lows of fluctuating bond prices get you down, there is another option. A GIC ladder could be a suitable alternative to short-term or even broad-market bond ETFs (like ZDB or the Vanguard bond ETFs). This is especially true when the yield-to-maturity (YTM) of the GIC ladder is higher than that of the bond ETFs, like it is now.

After back-testing this strategy over the same measurement period, we found the GIC ladder climbed to $104,473 (light grey line in the graph below), or 1.10% per year on average after-tax (with a much smoother ride than the bond ETFs). You could even consider combining GICs and ZDB in your taxable account, to ensure you have enough liquidity for rebalancing your portfolio. For more information on this strategy, please read: The Most Boring Battle Ever: Bond ETFs or GICs?

Sources: BMO Global Asset Management, NBIN, Vanguard Investments Canada Inc., cds.ca, taxtips.ca

Hi Justin,

Can you speak to the tax (in)efficiency of the equity part of all in one ETFs in a taxable account (specifically a CCPC) when the equities pay out distributions or when you sell? Does the fund specify which component (CDN vs US vs Foreign equity) the distribution is for? I know that taxation in a CCPC is different for each of those so I want to understand how this works or if you somehow avoid the taxation differences in the equity distributions because you used and all in one ETF.

Then when you sell, is a capital gains tax the same whether CDN vs US vs Foreign equity (if in all in one or individual ETFs)?

Thanks for your time!

@Stephanie – The tax implications of holding an all-in-one ETF in a CCPC would be similar to holding the underlying ETFs directly (i.e., all eligible dividends, foreign dividends, interest income, etc., would retain their character in both scenarios). Capital gains are also taxed the same way (currently 50% of the gain is taxable as income).

Thank you for your response!

My other question is with respect to using an ETF like VXC or XAW – since these hold different types of foreign equities in different proportions, do these funds automatically rebalance to keep the percentage of each in line with the targets (ie – 61.5% USA, Japan 6.3 %, China 3.6 %, Europe about 11.8%, etc)?

Based on advice from my accountant for my situation, he recommended that I try to keep as much Canadian in my CCPC as possible, then US and other Foreign equities in TFSA and favour bonds in RRSP. Up until now I have been transitioning out of TD series and using VIU and VEE in the TFSA since it only has so much contribution room and then in CCPC favouring VCN, but needing to use VIU, VUN, VEE for any “spill over” that won’t fit in the TFSA. Given how well the US Market has done, I want to get US into my TFSA and out of my CCPC as much as possible so I was thinking that I would lean toward CCPC favouring VCN (knowing there will still be “spill over” and then switching to VXC in TFSA to limit taxation from the corp and allow for more tax free growth from all foreign equity sources. Is there anything I’m missing in my thought process that I should consider? I have done so much reading and research and I think I have a good plan but I don’t want to get stuck in “Analysis “Paralysis”.

Thank you again for taking time to respond to these questions. Your videos, blogs and your answers to comments have been so incredibly important and are much appreciated!

Hi Justin,

This post (linked below) on the Rational Reminder forum from Wes Gray of Alpha Architect indicates that US-listed (or US-wrapped) ETFs have the flexibility to do custom create/redeem in their implementation. He also says that this leads to a tax-deferral benefit in taxable accounts that would more than offset losses due to the additional withholding tax a Canadian investor would be subject to by holding a Canadian-listed ETF instead. Is this something you have looked into yourself?

Note: RR community login required to view the post:

https://community.rationalreminder.ca/t/avantis-new-etfs-september-2021/9629/130

P.S. Any chance we might see you and/or Dan do CPM/CCP crossover episode of RR with Ben and Cameron sometime in the near future? I know you’re colleagues at PWL but I’d bet your different philosophies on some issues would make for a fascinating episode.

@Danny – I don’t have a login for this post, but if he’s comparing something like XEF to IEFA, the after-tax figures I’ve calculated in the past put XEF ahead of IEFA in taxable accounts (although the lower fees of IEFA do offset the majority of XEF’s withholding tax benefit).

We don’t have any plans for a crossover episode, but you never know.

Hello, had a question regarding dividend yield reporting in the context of foreign withholding tax. I was reading your white paper and saw calculations on tax percentage one will have to account for for US and international investments. I was trying to replicate your calculations and I am hoping you can help me understand a few key things I am missing.

You say dividends reported are “net of foreign withholding tax”. I take it to mean that dividends reported are AFTER tax paid (i.e. not gross). Therefore it follows that dividend yield reported is also net not gross (i.e. after tax). But this doesn’t seem the case when you calculate WHT in TFSA, where you multiply yield by Foreign Withholding Tax (15% for US and calculated from annual report for International). Shouldn’t the gross yield be multiplied by FWHT and not the net yield? What am I missing?

Thank you!

@Sam: Let’s say you’re holding a Canadian-listed U.S. equity ETF (like VUN) in your TFSA. VUN holds a U.S.-listed ETF (VTI) to gain exposure to U.S. equities.

We’ll assume the gross dividend yield on U.S. equities is 2.03%, and the expense ratio of VTI is 0.03%. We first subtract the expense ratio of 0.03% from the gross dividend yield of 2.03%, leaving us with 2.00% after VTI’s product fees. The U.S. will then withhold 15% of this gross (after fees) dividend, or 0.30% (2.00% x 15%). Vanguard US will then distribute the net dividend of 1.70% to Vanguard Canada, where VUN will take an additional 0.13% in annual fees (for total VTI + VUN product fees of 0.16%).

The investor will end up with an annual net dividend of about 1.57% (after foreign withholding taxes and product fees).

@Justin: Ahh I see! So the reported yield by VUN will be 2.03% gross on their annual report, not net. I was getting confused with the term “net of foreign withholding taxes”. I tried searching but cannot find an exact explanation? What does this represent?

@Sam: The gross dividend yield (before withholding taxes) is taken from the underlying index fact sheet (for the CRSP US Total Market Index).

Net of foreign withholding taxes would generally mean: after foreign withholding taxes.

@Justin: This must not be a common thing then… I was looking at VEA’s annual report for 2018, their report dividend distribution per ETF share was 1.244 of net income! So the yield calculated includes expenses and taxations. This is then net yield then no? Sorry for all these questions but it keeps nagging me. Thank you so much!

@Sam: That sounds like the net yield to investors (after FWT and expenses).

Ohh I think I was getting confused between ETF income yield and return as ETF holders.

Return will be income yield minus expenses and taxes as long as all the income is distributed, and this is what the calculations are estimating!!!

Is this general practise, some yield might be used for fund expenses other than ER and taxes. Got it?!!

@Sam: Sounds about right!

Hi Justin,

Will you be updating your Foreign Witholding Tax calculator to include ZGRO/ZBAL/ZCON?

I noticed these 3 have a tilt towards emerging markets which may or may not make them more tax inefficient, depending on how the underlying ETFs are structured.

You mentioned in a previous post that you will soon be “rolling out The Ultimate Guide to the Vanguard Asset Allocation ETFs.” I am wondering if you will talk about the iShares and BMO offerings too? (I personally favour the iShares asset-allocation ETFs due to the PACC eligibility, which makes it easy for people to automate their savings).

@Mark: I’ll definitely be updating the Foreign Withholding Tax calculator to include ZGRO/ZBAL/ZCON (probably within the next month). I would expect they will have similar withholding tax drag as the other asset allocation ETFs.

I will also be releasing guides for the iShares and BMO asset allocation ETFs too (so many ideas…not enough time ;)

Hi Justin, Great analysis as always. I was wondering whether you would consider pulling out different ETFs from the many asset classes that were analyzed, to form a portfolio, now that the tax pros and cons have been analysed.

@TW: The cost/tax benefits of breaking up the Vanguard Asset Allocation ETFs into individual ETFs are relatively large in an RRSP (so I will be releasing a blog shortly that will show investors a process for doing so, and the savings they can expect for the extra complexity).

Hi Justin,

Thanks for sharing your insight in this good article, through which I read your older post “Corporate Taxation: The Eggs-act Science of Capital Gains Taxation”. Getting capital gains is the most tax-efficient in a corporate account. However, if I want to have a steady stream of income from corporate account investments, should I be investing mostly in Canadian stocks/ETFs that pay high dividends? Those stocks/ETFs will also provide capital gains in the long run. Do you think this is the “best of both worlds” approach in that I can flow through dividends annually to my personal account and can also realize capital gains in the long term? Thanks for your advice in advance.

@Joe: High dividend strategies are generally less diversified, less tax-efficient and more expensive than broad-market ETFs. Keep in mind that even a broad-market Canadian equity ETF currently has a dividend yield of over 3% (so you’re already expected to receive the “best of both worlds”).

However, if a high dividend ETF strategy helps to keep you invested for the long term from a behavioural perspective, it may be a decent alternative to broad-market ETFs.

I am invested evenly in VBAL and VGRO. Together, these give me the low-fee 70/30 asset allocation I want for my total portfolio. This is in both my registered and non-registered accounts. If I were to shift more VBAL to RRSP to mitigate the tax “drag”, I understand this would be more tax “efficient.” But couldn’t the taxes overall be higher if the equity-heavier VGRO generates a lot more total income? I might save 10 basis points in drag but the difference in performance between the two would not be tax sheltered.

Any thoughts on how to optimize this?

@James – The asset location topic is much more nuanced than this. I will be releasing a series of videos over the next few months which will attempt to shed more light on this complicated process.

Hi Justin, did you get around to releasing that series on asset location? This is where I’ve been hung up on. Where the optimal account location is for each friend that I buy. Thanks

@Adam – I’ve been releasing the asset location videos/blogs over the past few weeks:

Asset Location – Part 1: Key Concepts | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQBpRLlEmGg

Asset Location – Part 2: The Ludicrous Strategy | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ScoLiJOeL6A

Asset Location – Part 3: The Plaid Strategy | Coming Soon!!

Hi Justin, thank you for this blog. It is very useful.

What would you suggest as a strategy if someone would like to sell a large amount of canadian-listed ETF (lets say ZSP) to buy a US-listed equivalent ETF (lets say IVV).

I find it risky to sell all ZSP, do a Norbert’s gambit, wait 3 days and buy IVV.

(A lot can happen on the market in 3 days … like last week)

Thank you

@Philippe: If you’re with a brokerage that allows you to place the ZSP sell, DLR buy, DLR.U sell, and IVV purchase on the same day (like RBC Direct Investing or BMO InvestorLine), this is your safest option (from an opportunity cost standpoint).

Alternative, if you have bond ETFs in your RRSP, you could consider selling these and converting the proceeds to USD using the gambit. Once the funds have been converted, you could then sell ZSP and immediately buy IVV.

Other than those options, there will unfortunately be a risk of being out of the market for a few days.

Thanks very much for the interesting post. I was just thinking about the interest payouts from bond ETFs today since it came up in Andrew Hallam’s Expat Millionaire. I’m also an expat in Germany and was hoping you could shed some light on a question I have about taxation.

Obviously I would pay withholding tax on the dividends from equity funds. As for interest from a Canadian savings account, this isn’t taxed at all as a non-resident. So I’m wondering whether the interest that’s paid out from a bond ETF would be treated the same as bank account interest. If so, does that mean that bond ETFs or a Vanguard AA ETF with a bond portion would be particularly tax efficient?

Let me know if I’m way out in left field… Thanks!

@Cody: As far as I understand, expats in Germany are taxed on their worldwide income, so Canadian savings account interest and bond interest would be taxable, even if no withholding taxes are applied: https://www.expattax.de/foreign-income-germany/

In terms of non-resident withholding taxes on Canadian-domiciled ETFs, a few of our non-resident clients hold the BMO Discount Bond Index ETF (ZDB) in their taxable accounts, and 25% is withheld from each distribution. Likely, all ETF distributions are just treated like dividends (regardless of their income breakdown).

Justin,

Thank you for timely commentary on the nuances of index investing. I have a follow up questions based on the scenario described above. For someone in the highest tax bracket in Ontario, would mild-leverage in the taxable (margin) account offset the drag from more conservative portfolio? I’m assuming the margin-interest to be written off at marginal tax rate. This may preserve simplicity of holding single asset allocation ETF. Thank you.

@Kundan Thind: I don’t feel leverage is a solution to the premium bond issue in taxable accounts. Without knowing the future after-tax return of the conservative portfolio vs. the after-tax cost of the leverage, you’re really just creating a potentially bigger problem.

I have a quick question. I`m hoping I`m on the right path.

My portfolio is currently 25% VCN (taxable), 13% XAW (taxable), 37% XAW (TFSA), 19% ZDB (taxable), and 6% ZAG (RRSP).

That’s a 25/75 fixed/equity split. Is that a good portfolio setup? Is the asset location good enough?

Looking forward to any insights or advice you can provide!

@Drew: I can’t comment on your asset allocation (as this would be specific to your personal goals and risk tolerance), but the asset location seems reasonable (i.e. equities in the TFSA first, equities in the taxable account next, fixed income in the RRSP, additional fixed income in a tax-efficient bond ETF like ZDB in the taxable account).

Hi Justin,

First, since this is my first post although I’ve been reader for a few years now, I want to use this opportunity to say thank you for this website and all the work you put in it.

I’ve been an index investor for about 15 years, but to make a long story short, I don’t wish to deal with rebalancing anymore so with the low fees of the asset allocation ETFs, in the last few months I switched 67% of my RRSP in a mix of XGRO, VGRO and ZGRO. The remaining balance (except for my 5% “discretionary funds”) is in VAB, VCN, and the US ETFs VT and AOA (iShares Core Aggressive Allocation ETF). The reason I purchased AOA and VT is that I didn’t want to convert back my USD to CAD, and I basically rebalance the whole with VAB and VCN (yes still some rebalancing work to do!).

I’m fine with paying the higher MER to not have to deal with rebalancing as much as I use to (I had a lot of ETFs as I was investing under both “pure” indexing and Fama-French models), but I have been having second thoughts about withholding taxes since I now have funds of funds.

I’ve just used your excel calculator (thank you gain) and I’m now confortable that I can live with the withholding taxes difference, but I’m still wondering how to calculate withholding taxes for AOA. AOA being a US ETF holding US ETFs, is it the same then holding directly the various ETFs, or will it end up like having one US Equity ETF, or something else?

@Patrick S: Thank you for reading the blog all these years (and for taking the time to post for your very first time).

AOA’s foreign withholding tax drag in an RRSP would be similar to holding the underlying U.S.-listed ETFs directly. I would estimate the FWT drag at around 0.12% in an RRSP – similar to VT’s tag drag in the CPM Foreign Withholding Tax Calculator.

Thank you Justin. With your answer, I was able to calculate that my portfolio has management fees of 0.19% and a drag of 0.16%, for a total of 0.35%. Using your calculator, I can see that I could optimize (using my USD and CAD RRSPs) and get management fees at 0.07% and drag at 0.08% (total 0.15%). So I’m paying 0.20% to, using your words, help me maintain discipline.

It’s more than I realized initially, especially if I look at the compound costs over 25 years. I still feel that I need to simplify my life right now, but maybe I will look at different areas and ways to simplify and in a few months switch to an optimized but requiring time and discipline portfolio.

In any event, I’m glad that I now know the real costs, and I would not have been able to figure it out without your calculator and your help, so thank you again.

Hi Justin,

Again, a wonderful and comprehensive study which should be very useful to all DIY investors.

On the GIC ladder, specifics are missing, as interest rates are radically different than in the four year period you profiled. We limited ourselves to a 3-year ladder in July 2018, with rates 2.26%, 2.66% and 2.94% at BMO, where rates are now 2.21%, 2.33%, 2.40%, 2.41% and 2.47%, making any GIC ladder practically useless.

That’s where our investments lie, so brokerage returns are lousy. On the outside, just before RRIFs kicked in, we bought 3-year GICs at 3.05%, which are with Oaken, and expire in August 2020.

Income from RRIFs goes to taxable accounts, so fixed income net returns are hugely important, and with interest income fully taxable and inflation of 2%, what’s a body to do?

If you could detail the rates and periods you used in your GIC ladder, it would make for a clearer contrast with the asset-allocation and discount bond tax factors you have provided.

Many thanks for your ongoing contributions to our investment knowledge.

@Davie215: “Interest rates are radically different than in the four year period you profiled”.

The rates on the GICs (at NBIN) at the beginning of the measurement period (December 31, 2014) were:

1 year = 1.75%

2 year = 2.11%

3 year = 2.17%

4 year = 2.37%

5 year = 2.58%

Average = 2.20%

The current GIC rates are slightly higher than they were during the measurement period (NBIN GIC rates as of June 6, 2019):

1 year = 2.20%

2 year = 2.34%

3 year = 2.45%

4 year = 2.55%

5 year = 2.60%

Average = 2.43%

In comparison, the yield-to-maturity (which is the best expectation of future bond returns) on the iShares Core Canadian Universe Bond Index ETF (XBB) on December 31, 2014 was 2.22%. It is currently hovering around the same range, at 2.13%.

Hi Justin,

Thanks for your great work! So would you say the overall difference in portfolio btw say vgro and breaking things apart and using a gic ladder be roughly 0.13%?

(1.1-0.81%)/(1-.535)=0.64

0.64 x 0.2 = 0.13%

Or did I get my math wrong?

@Jon: You’re very welcome – I’m glad you’ve enjoyed the article!

It’s difficult to know going forward what (if any) return advantage a GIC ladder would have over VAB/VBU/VBG.

One way would be to first compare the current 2.05% yield-to-maturity (YTM) of ZDB with a ladder of GICs (which are currently yielding around 2.43%). The expected before-tax return advantage in this example would be around 0.38% (2.43% minus 2.05%).

We could then add this 0.38% figure to our 0.25% estimated before-tax return advantage of ZDB vs. VAB/VBU/VBG, giving us a total estimated before-tax return advantage of 0.63%.

Taking VGRO’s 20% allocation to fixed income would result in an overall estimated before-tax return advantage of GICs vs. VAB/VBU/VBG in VGRO of 0.13% (0.63% x 20%).

Assuming an Ontario top rate taxpayer, the after-tax advantage of GICs vs. VAB/VBU/VBG in VGRO would shrink to around 0.06%.

Thanks for the GIC ladder rates, which are not as different as I assumed versus current rates. With the four and five year rates at BMO that I cited, the question becomes:

Why make a 5-year ladder, rather than a 3-year one with such paltry returns for locked in money over this period. Would the comparative revenue from a dividend yield make more sense in lieu of fixed income beyond the 3-year mark in a taxable account — using your premise of the low & taxable interest rate being a discouragement?

We have substantial maturing GICs next month in our RRIF moving to taxable accounts, where rebalance of our asset mix could only be avoided by buying FI with these proceeds. Both GICs and discount bonds don’t seem like a good idea for these proceeds?

@Davie215: The investment risks of GICs vs. equities is not equivalent, so they are not replacements for one another (whether or not the dividend yield on the stocks is similar to the interest yield on the GICs). You should first decide on your asset allocation – then you can decide which securities are the most appropriate to hold within each asset class.

If you already have a target asset allocation, the fact that your GICs are maturing shouldn’t be an issue (you would just reinvest them in whichever asset class is underweight – likely fixed income). If you don’t have a target asset allocation, you should determine this first before making any other decisions on security selection.

A 1-5-year ladder can reduce the reinvestment risk if fixed income yields decrease (as they just did). It also tends to have a higher expected return than a 1-3-year ladder.

I do have an asset allocation of 35% to fixed income, with IPS seeking 2.25% on FI and 5% on equities, and the drop in FI rates from previous buying periods is causing me to wonder if locking in for 0.05% expected return gain for 5-years is pointless, when the final two years adds such a puny amount.

No one can predict rates at mid 2022, but I’m thinking 2.41% ain’t worth a locking in.

To boost the risk with extra equities and judging dividend income at comparable rates to FI, while enjoying much-preferred tax treatment over FI in taxable accounts (that get the GIC RRIF proceeds) seems to be worth considering.. Dividend-growth mavens to the G&M columns completely discount the market price as irrelevant on a hold-forever strategy, claiming the yield provides tax-favoured income superior to that from FI holdings.

Recognizing the risk factor already, are these dividend income fans missing something — that’s the point under consideration for a potential altering of my approach.

I could, of course, pull the RRIF proceeds to move to another provider, like EQ Bank or more money to Oaken, where GIC rates are distinctly better than within the brokerage offerings?

Yup, I’m contradicting my own IPS bypassing current GICs that parallel my stated targets, but once those RRIF payments need to be reinvested in taxable accounts, the yield goes to zero after tax and inflation hits, regardless of discount bonds, bond fund ladder or GICs. My partnership with the CRA gives it all away, and keeps nothing. This is the dilemma for me.

First of all, I just wanted to say thank you to Justin for all your work in creating and managing this blog. I learned a lot from this blog about the passive investment strategy.

I was wondering if you have have any explanations as to why VBU and BND have significant differences in total returns even though they both hold the same US bonds.

As per Morningstar,

Total Return %

3-Year VBU (NAV) 1.29%

3-Year BND (NAV) 2.88%

And taken from factsheet from Vanguard websites,

Factsheet | April 30, 2019

3 year VBU Net asset value (NAV) total return 1.10%

Factsheet | March 31, 2019

3 year BND Net asset value (NAV) total return 2.00 %

And with this significant tracking error, is it worth holding VBU in the portfolio (as is the case in the Vanguard all-in-one portfolio VCNS/VBAL/VGRO)?

Oops, please disregard the last question, as the answer is well explained in your blog post. I should’ve read more carefully the first time.

@David: My last response was incorrect (sorry about that…I must not have had my coffee for the day).

I’ll follow-up with a blog post to better answer your question (as it’s a great one!).