We’ve now covered just about everything you need to know about investing in total U.S. stock market ETFs, including a general comparison among four solid choices, as well as a discussion about the foreign withholding taxes involved.

By now, you might be asking yourself:

“If the product costs and foreign withholdings taxes on dividends are reduced by holding U.S.-listed U.S. equity ETFs in an RRSP, why not just buy VTI or ITOT, instead of VUN or XUU?”

And if there were no costs to convert your loonies to U.S. dollars (and back again), you’d be on the right track. But we haven’t yet touched on some of the biggest costs facing Canadian investors purchasing U.S.-listed ETFs. These are the high currency conversion fees levied by their brokerage.

Currency Conversion Fees in RRSPs

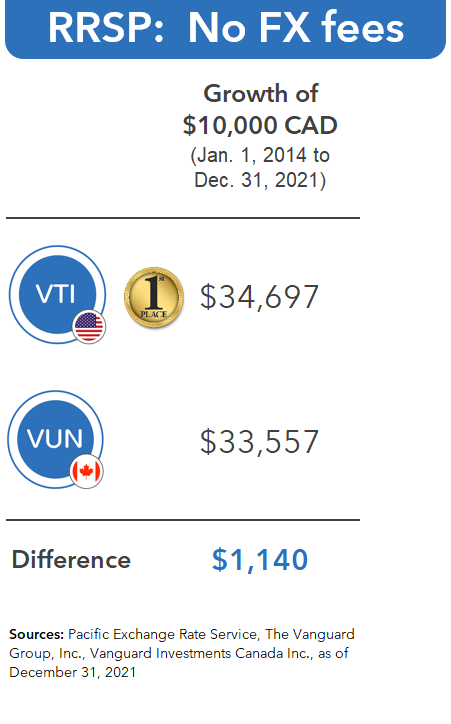

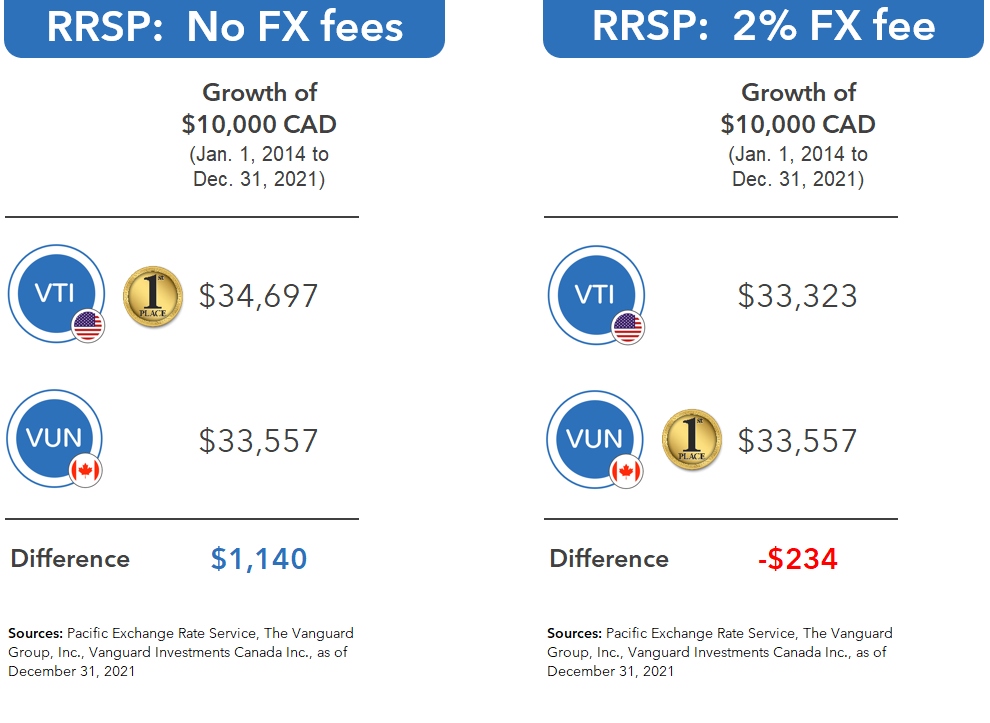

For example, let’s compare a $10,000 Canadian dollar investment in VTI and VUN within an RRSP. We’ll start both investments on January 1, 2014, which was the first full calendar year after VUN launched, and run through the most recent year-end. Across this period, we’d find that VTI did in fact grow at a faster rate than VUN, due to its lower product costs and the elimination of the 15% withholding tax on U.S. dividends received in the RRSP.

But there’s a catch. We’ve assumed there were no costs to initially convert $10,000 Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars to purchase VTI, and also no costs to convert those U.S. dollars back to Canadian dollars when you ultimately sell your VTI shares.

In reality, Canadian discount brokerages typically charge currency conversion fees of 1% to 3%. You won’t see this cost listed on your account statements, but the brokerage is basically taking a hidden commission during the transaction. This clever ruse is accomplished by adjusting the retail currency conversion rate the brokerage offers to their clients.

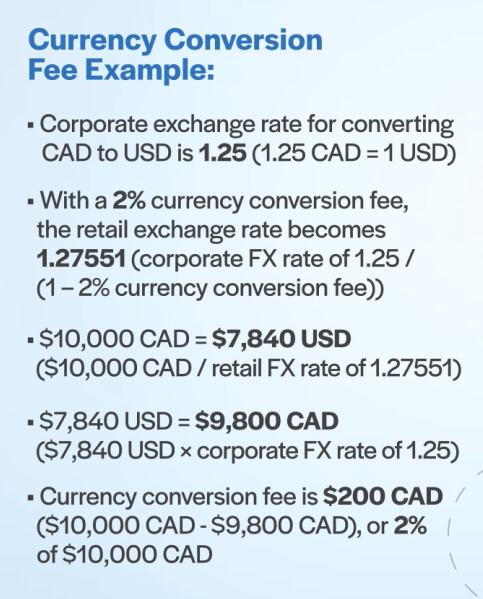

To illustrate: Let’s assume a brokerage can convert Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars at a favourable corporate rate of 1.25. This means that 1.25 Canadian dollars are truly worth around 1 U.S. dollar. Now that’s what it costs them. But to earn a 2% currency conversion fee from their clients, they would offer you a higher retail exchange rate of around 1.27551. This is calculated as the 1.25 corporate rate divided by (1 – their 2% currency conversion fee).

So, if you handed your brokerage $10,000 Canadian dollars, they would hand you back $7,840 U.S. dollars (or $10,000 Canadian dollars divided by the retail exchange rate of 1.27551). Seems okay so far, right?

But how much are those $7,840 U.S. dollars really worth in Canadian dollar terms? If we multiply our $7,840 U.S. dollars by the “fair” corporate exchange rate of 1.25, this gives us $9,800 Canadian dollars. Even if you’re not a math whiz, you may notice that’s $200 Canadian dollars, or 2% less than the $10,000 Canadian dollars we started out with.

See how easy it is for these currency conversion fees to go unnoticed?

If that’s not frustrating enough, you take another hit on the way back, when you sell your VTI shares and convert your U.S. dollars back to loonies. In our 2% currency conversion fee scenario, any benefits from holding VTI instead of VUN in an RRSP would end up being significantly reduced during the measurement period.

The message is clear: The fee and tax advantages of holding U.S.-listed ETFs in an RRSP don’t count for much if your broker gouges you on currency conversion fees in the process.

Currency Conversion Fees in TFSAs

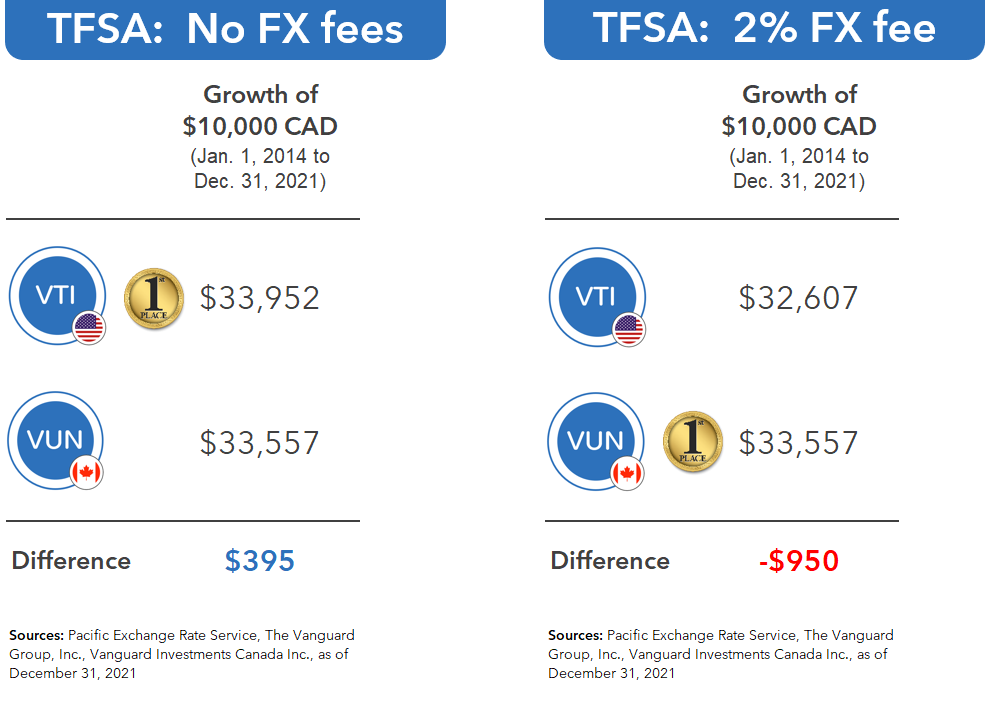

This issue becomes even more onerous in TFSAs, where foreign withholding taxes can’t be eliminated by opting for U.S.-listed U.S. equity ETFs, like VTI, over Canadian-listed U.S. equity ETFs, like VUN. Here, you can get slammed with both the taxes and the hidden fees.

In a perfect world with no currency conversion fees, the lower product costs of VTI vs. VUN would have resulted in slightly more growth for VTI over our measurement period. However, if we assume a 2% currency conversion fee on the front-end purchase and back-end sale of VTI, we find VUN to be a much better option for these account types.

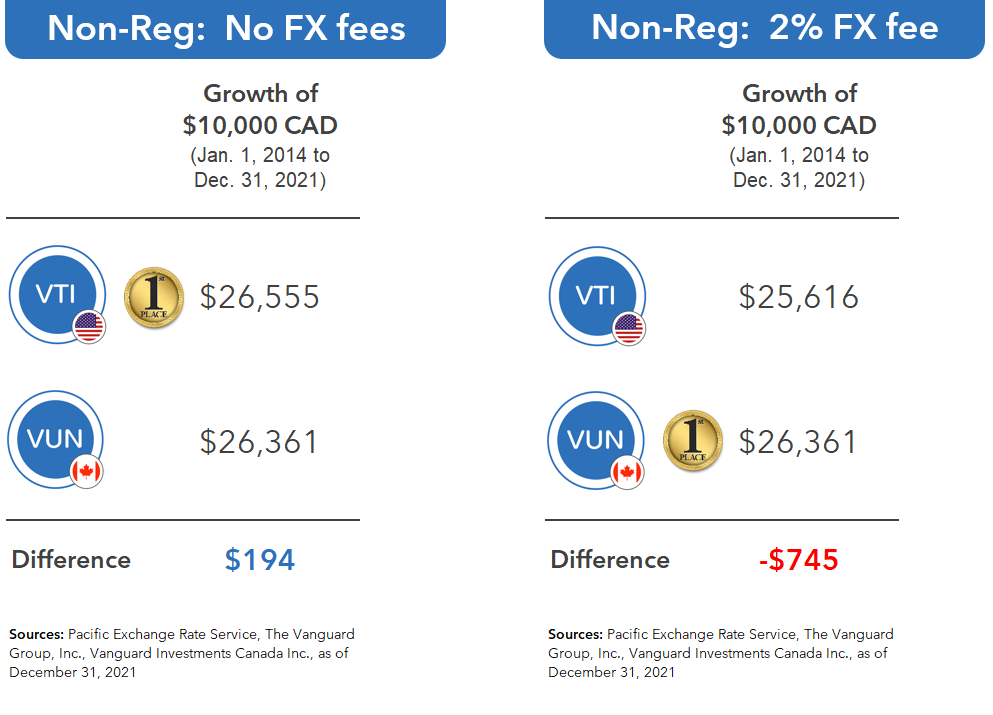

Currency Conversion Fees in Non-Registered Accounts

Last up, there’s our non-registered account comparison. Here, we’ll assume all units of each ETF are sold at the end of the measurement period, and the investor pays taxes at the top Ontario tax rate. If we first assume no currency conversion fees, we find VTI and VUN had similar after-tax growth over the measurement period. But once we tack on a 2% currency conversion fee to the purchase and sale of VTI, we find VUN to again be the superior choice for non-registered accounts.

In future videos, I’ll show you one way you can avoid your brokerage’s steep currency conversion fees, through a strategy called Norbert’s gambit. However, Norbert’s gambit is not without issues of its own. So for now, my advice would be to just stick with Canadian-listed ETFs and avoid U.S-listed ETFs altogether.

Thank you for the great article, Justin.

After transferring my wealth simple invest account to quest trade, in kind, I found that a number of the ETFs held within it were US listed ETFs. My plan was to sell the wealthsimple holdings once I got them in Questrade and purchase a single asset allocation ETF for my investments. This will leave me with USD cash in my account. I don’t want to pay a currency conversion fee, and I am unfamiliar with Norbert’s gambit. Is there a US listed etf or etfs that I could purchase with that USD that would align with XGRO. Or is there another strategy you would recommend?

Thanks for any insight

Thanks for the article, Justin. This info is not easy to come by when navigating the DIY space, in my experience.

I recently decided to go DIY and transferred “in kind”, my Wealthsimple Invest LIRA and RRSP to Questrade. I intended to go the route of purchasing a single asset allocation ETF (XGRO) through questrade but found that my Wealthsimple invest account contained several USD ETFs. I’m aware that selling these and buying XGRO will cost me in the currency conversion (1.45% according to questrade)

Would it make sense to purchase a U.S. ETF that is roughly equivalent to XGRO in terms of asset mix and risk, rather than selling the US ETFs and buying XGRO?

Thanks

@Chris Brown – If the USD holdings in your RRSP are modest (i.e., below $50,000), you could consider just taking the one-time currency conversion hit. If they are above this amount, it might be worth it to learn the Norbert’s gambit strategy.

Complicating your portfolio with individual U.S.-listed ETFs (instead of XGRO) doesn’t sound like an ideal solution.

Thanks, Justin. Useful info as always.

When capturing the currency conversion in a tax return, it’s my understanding that CRA requires that we use the Bank of Canada rate in effect on the day of the conversion (or the average rate for regular conversions throughout the year). Would this make matters worse, or at the very least, mean that the embedded 2% fee in the poor conversion rate, is a cost that cannot be claimed?

@Bob Wen – If you buy $10,000 CAD of VTI in a Canadian dollar non-registered account, your account statement will show a $10,000 CAD purchase price/cost base (which is your true cost base for tax purposes), even though your actual market value is technically $9,800 CAD (so you technically have a $200 capital loss due to the FX fee).

It’s only when you purchase a U.S.-listed security in a U.S. dollar non-registered account that you need to convert the cost base to CAD using the FX rate on the settlement date for tax purposes.

Thanks for the breakdown, in the case of US equity it seems unlikely there is a benefit to holding VTI. More compelling is Emerging Markets where holding VWO instead of VEE in an RRSP saves 49 bps (37 bps in FWT and 12 bps in MER). IEMG and XEC tell a similar story with 45 bps in savings. If you get unlucky with Norberts Gambit, or do a small amount I could see this benefit disappearing.

I would love to see a deep dive into Norberts Gambit, taking fx changes, ecn fees, commissions, and opportunity cost (being out of the market for a few days) all into account.

@Jamie – I will be comparing IEFA/XEF and IEMG/XEC in future videos.

As for Norbert’s gambit, if an investor was very diligent (and could avoid trading commissions and any opportunity costs of the gambit process), then holding VTI in an RRSP would be the superior choice. Unfortunately, there’s no way to run an analysis of the opportunity cost, as this will depend on what markets do during the waiting period.

Regarding gambit trades at NBIN, it was my understanding that PWL had access to FX rates at NBIN that were more cost effective than what could be realized with Norbert’s Gambit. This was what the PWL team in Ottawa told me about 18 months ago.

@Kyle – It would depend on the amount of the FX conversion. I’ve converted large amounts for clients (i.e., $5,000,000) and received a better rate with NBIN compared to Norbert’s gambit. But for more modest amounts (i.e., $100,000), Norbert’s gambit is generally a better option.

Thanks, as always, Justin for your incredible service to the community.

I just wanted to share that I am a big fan of using Interactive Brokers as my brokerage firm, mainly due to the currency conversion costs. For currency conversions, they charge a fee of only 0.002% – yes, 1/1000th of the 2% you use as an example here! I had to check it multiple times to make sure but it has worked for me consistently.

@Jeremy – Thank you for sharing your experience. I’ve yet to use Interactive Brokers for RRSP FX conversions, so I’ve never compared the rate to Norbert’s gambit or the banks.

Thanks for the clear comparison. I will reference this in my blog.

This offers a nice segway into Norbert’s Gambit.

Even with Norbert’s gambit, I opt to keep VUN instead of doing a conversion to hold VTI, especially given the low MER of VUN. Complexity comes at a cost, and I find that cost to be too high to merit the use of VTI.

@Jake – I would agree with you on using VUN instead of VTI. With our client portfolios at NBIN, we are able to process all gambit transactions on the same day, so there’s no risk of being out of the market for any period of time (so we use U.S.-listed ETFs in our clients’ RRSPs, but still recommend DIY investors avoid them).