There’s never a lack of free advice in this world. If you’re determined to get in shape, for example, you can find any number of infomercials touting THE fitness equipment, diet plan or video series guaranteed to give you Zac Efron’s six-pack abs … or your money back.

Except each of us is different, with different goals, and varying amounts of effort we’re willing to exert. Zac’s six-packs don’t come easy, which is why I’ve been known to sometimes sacrifice my own workout to an actual cold beer on a hot summer day. I can live with that.

Investing is no different. There’s an endless supply of opinions ranging from clear, to confusing, to downright contradictory. As with your physical fitness, beware of anyone offering wholesale guarantees. Your own best investment strategy hinges on your personal goals and circumstances. It’s also worth being realistic about how much effort you’re willing to expend to whip your portfolio into perfect shape.

Take asset location – or in which accounts you’ll hold your portfolio’s various asset classes. Ideally, we want to locate tax-inefficient assets in tax-preferred accounts and tax-efficient assets in taxable accounts. But there are so many squirmy details, and only so much wiggle-room in your accounts. No wonder there is considerable debate on how to achieve optimal asset location.

As I’ll demonstrate today, a couple of considerations can clarify things. First, I believe it usually makes the most sense to consider your results post-tax; that’s the money you’re actually left with after the dust settles. Second, I would suggest that the bigger driver behind your post-tax worth is usually your post-tax asset allocations (i.e., what percentage of your total portfolio you want to assign to various asset classes, regardless of account location).

Now, circle back to also basing your “correct” choice on where you fall along the spectrum of practical vs. perfected solutions. This should help you mull over how much or little you want to meld your account-based asset location choices into your portfolio-wide asset allocation decisions.

To illustrate what I mean, let’s run through some asset location choices you might make between your essentially tax-free TFSA and tax-deferred RRSP accounts. I’ll use three post-tax asset allocation scenarios as our guides.

- Option #1 scenarios target a post-tax, 55.56%/44.44% equity/fixed income asset allocation mix

- Option #2 scenarios flip to a post-tax 44.44%/55.56% equity/fixed income mix

- Option #3 scenarios explore ways to arrive at a post-tax 50/50 mix

Once we’ve taken the grand tour, I’ll wrap with an overview of potential next steps you can choose from, depending on your personal tastes.

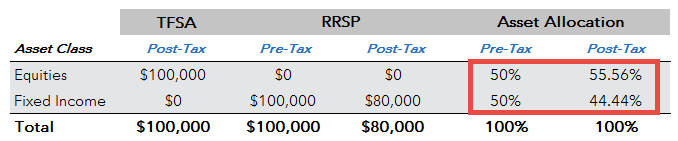

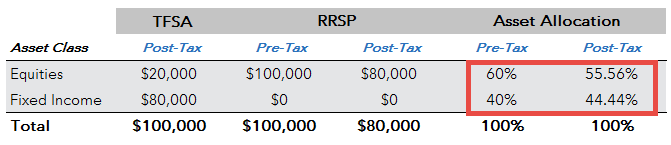

Option #1 (a): Equities in the TFSA first (ignore post-tax asset allocation)

Pre-tax asset allocation: 50% equities / 50% fixed income

In this scenario, we’ll ignore the fact that the government owns part of your RRSP. This is the traditional approach taken in my recent asset location blog post, and is one of the most common approaches to managing a portfolio.

Assuming that the TFSA and RRSP are each worth $100,000, we would purchase $100,000 of equities in the TFSA and $100,000 of fixed income in the RRSP. The argument here is that investors never pay any tax on growth or dividends in a TFSA (except foreign withholding tax), so they should hold their highest-expected-growth investments there first … i.e., their equities.

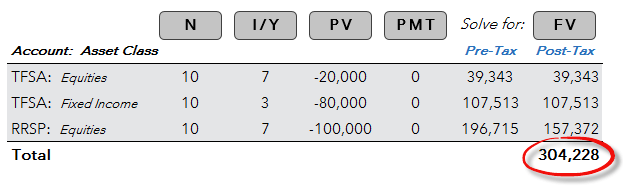

If we assume 7% and 3% annualized returns for equities and fixed income, respectively, and an effective tax rate of 20% on the RRSP value at the end of the 10-year measurement period, we would end up with a portfolio worth $304,228 post-tax.

(Note: For this and subsequent scenarios, I’ve kept it simple by assuming no portfolio rebalancing. Although the values would change if we incorporated annual rebalancing, the overall concepts would not. I also wanted to ensure that those who wanted to crunch the numbers could easily follow along with their financial calculators, so I’ve included the calculator inputs below each example.)

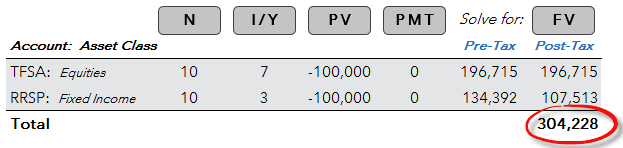

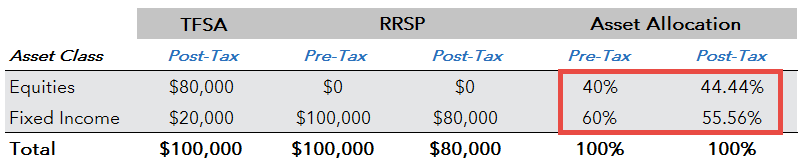

Option #2 (a): Equities in the RRSP first (ignore post-tax asset allocation)

Pre-tax asset allocation: 50% equities / 50% fixed income

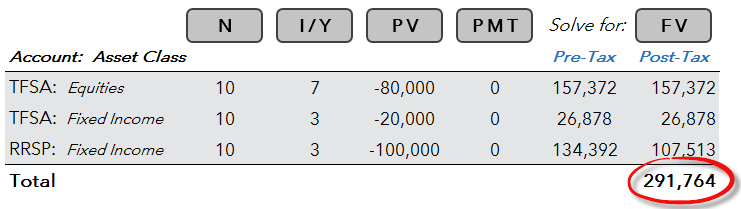

For our next comparison, we’ll swap the account location of the two asset classes, holding equities in the RRSP first.

Using the same assumptions as Option #1 (a), we discover that the post-tax portfolio value after 10 years is only $291,764 (or $12,464 less than our first example). It would appear that investors who prioritize equities in their TFSA first are expected to end up with a higher post-tax portfolio value (assuming equities outperform fixed income, as they are expected to do over the long-term).

The Secret Is in the Allocation Sauce

Your astute eye may have already noticed an issue with this comparison. Although the pre-tax asset allocation for both options is 50% equities and 50% fixed income, the post-tax asset allocations differ considerably. Option #1 (a) has a more aggressive asset mix of 55.56% equities and 44.44% fixed income. Option #2 (a), on the other hand, has a more conservative asset mix, with only 44.44% being allocated to equities, while 55.56% has been allocated to fixed income.

By assuming that you can default on the government IOUs you wrote over the years while maxing out your RRSP, you may be inadvertently taking more or less risk than you had intended (from a post-tax perspective). Only a portion of the RRSP is actually yours to keep (while the TFSA is 100% yours), so placing equities in the RRSP first (instead of your TFSA) will make your post-tax asset allocation less aggressive (and vice-versa).

The takeaway: As I touched on before, it’s the higher post-tax asset allocation to riskier equities that is expected to result in a higher post-tax portfolio value at the end of the measurement period for Option #1 (a). So, it’s the asset allocation, not the asset location, that’s the driving factor behind the different results.

If both investors adjusted their pre-tax asset allocation so that their post-tax asset allocations were equal to those in Option #1 (a) and Option #2 (a), it wouldn’t matter whether they held equities in their TFSA or RRSP first. Their ending post-tax portfolio values would be equivalent to any portfolio set-up that had the same post-tax asset allocation.

If you don’t believe me, let’s take a look at the numbers.

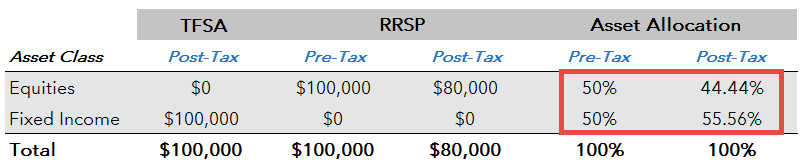

Option #1 (b): Equities in the RRSP first

Post-tax asset allocation: 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income

In this next example, we’ve assumed that our investor is targeting a 55.56% equity, 44.44% fixed income post-tax asset allocation. This is the same post-tax asset allocation as in Option #1 (a), which resulted in a post-tax portfolio value after ten years of $304,228. But unlike the asset location set-up in Option #1 (a), they have decided to hold equities in their RRSP first. Because the government owns 20% of this account, the investor will need to have a more aggressive pre-tax asset allocation of 60% equities and 40% fixed income to generate the same post-tax asset allocation. (Note: As you’re moving through these illustrations, you may find it helpful to reference the summary chart I’ve included near the end of the blog post.)

After 10 years, we find that the post-tax portfolio value is exactly the same as in Option #1 (a): $304,228.

You may notice, however, that although the post-tax asset allocation in this example is the same as in Option #1 (a), the investor had to increase their pre-tax equity allocation by 10% (from 50% to 60%). Although I would like to think that all investors are rational (i.e. they realize that Option #1 (a) is identical to Option #1 (b)), the next market downturn may cause Investor #1 (b) to abandon their investment plan, while Investor #1 (a) may keep a much more level head during the market drop.

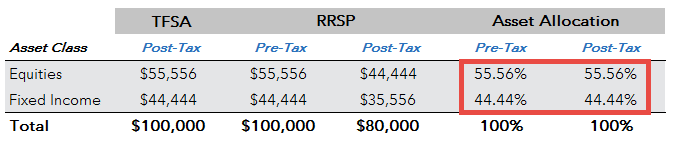

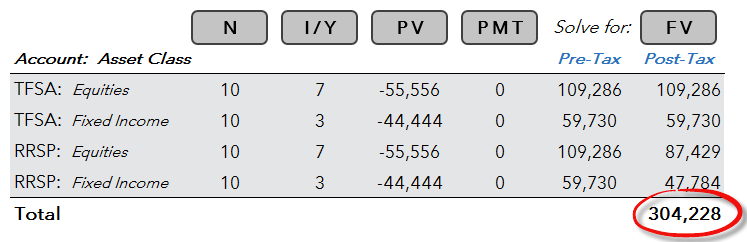

Option #1 (c): Same asset allocation across both accounts

Pre- and post-tax asset allocation: 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income

This is another common asset location set-up for investors. Instead of racking your brain over all the details (most of which are unpredictable anyway), you could simply hold your desired asset allocation across both accounts in the same proportions. This ensures that your pre- and post-tax asset allocations are always equal. Asset allocation ETFs are great solutions for this path of least resistance, since they automatically rebalance for you.

By allocating 55.56% of equities to the TFSA and RRSP, and 44.44% of fixed income to the TFSA and RRSP, the post-tax portfolio value at the end of 10 years is also an identical $304,228 (the exact same value as in Option #1 (a) and Option #1 (b)).

Just so we know this wasn’t a fluke, let’s change the asset locations for Option #2 (a) from our example above, keeping the post-tax asset allocations constant.

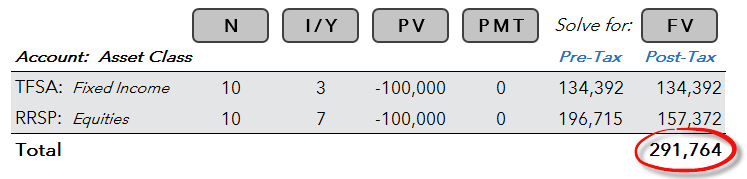

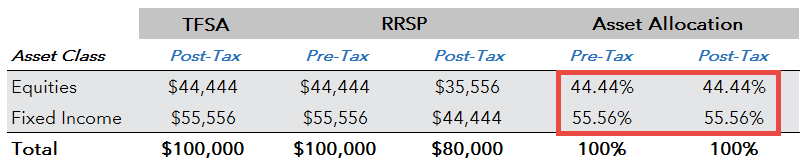

Option #2 (b): Equities in the TFSA first

Post-tax asset allocation: 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income

In Option #2 (a), the investor held equities in their RRSP first and ended the 10-year period with a post-tax portfolio value of $291,764. The proposed reason for the lower-ending portfolio value was that the investor had a more conservative post-tax asset allocation of 44.44% equities and 55.56% fixed income (compared to Option #1(a) with its 55.56% equities and 44.44% fixed income post-tax asset allocation).

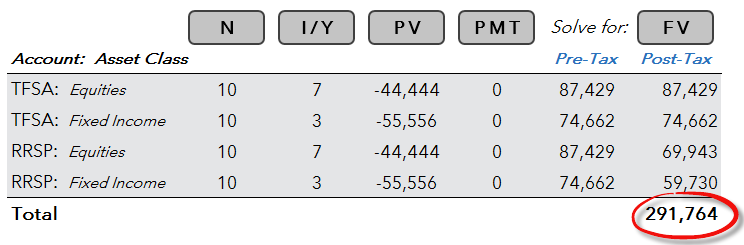

Now let’s test this claim by instead holding equities in the TFSA first, but maintaining the same post-tax asset allocation as Option #2 (a). For this, the investor would need to have a pre-tax asset allocation of 40% equities and 60% fixed income. (See chart below.)

In this scenario, the decision to hold equities in the TFSA first resulted in a post-tax portfolio value after ten years of $291,764 (the same as Option #2 (a)). The investor was also able to pull off a more conservative pre-tax asset allocation than our investor in Option #2 (a). For anxious investors who need help staying the course during downturns, this may be a more desirable asset location to consider.

Option #2 (c): Same asset allocation across both accounts

Pre- and post-tax asset allocation: 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income

As with Option #1 (c), holding identical pre- and post-tax asset allocations across your TFSA and RRSP resulted in the identical $291,764 post-tax portfolio value at the end of the ten year period.

And just so we can really hit the point home – that it’s your post-tax asset allocation that determines your ending portfolio value, not your asset location decisions – let’s look at a final example of an investor who is targeting a post-tax asset allocation of 50% equities and 50% fixed income.

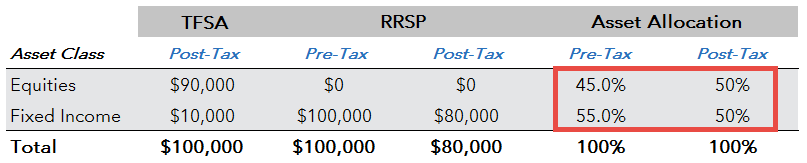

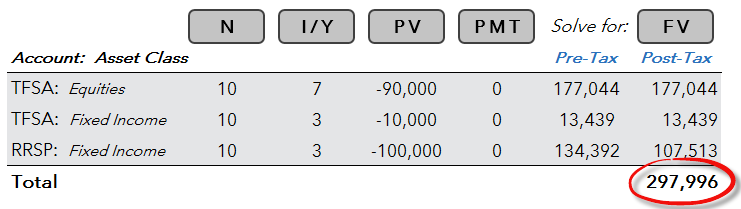

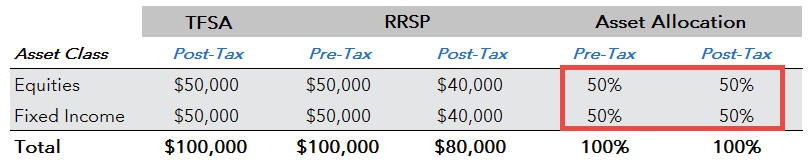

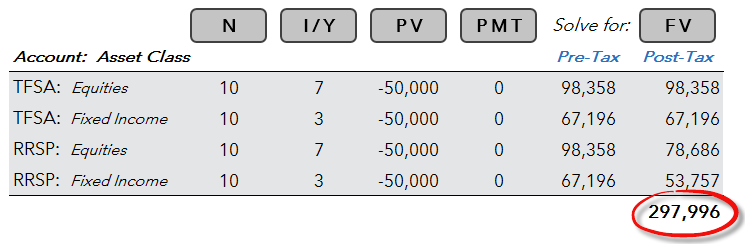

Option #3 (a): Equities in the TFSA first

Post-tax asset allocation: 50% equities / 50% fixed income

If the investor wants to hold equities in their TFSA first (and still maintain a 50/50 post-tax asset allocation), they would need to change their pre-tax asset allocation to 45% equities and 55% fixed income (a more conservative pre-tax asset mix). The post-tax portfolio value after ten years would be $297,996. With asset allocations still driving the bus, it makes sense that the end results of a post-tax 50/50 mix would be a little higher than a post-tax 44.44%/55.56% equity/fixed income mix ($291,764), and a little lower than a post-tax 55.56%/44.44% equity fixed income mix ($304,228).

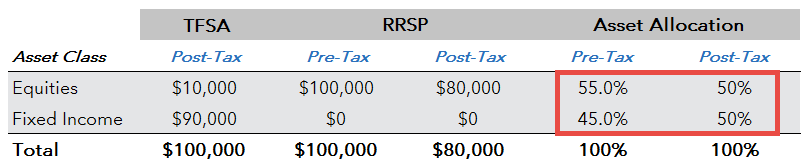

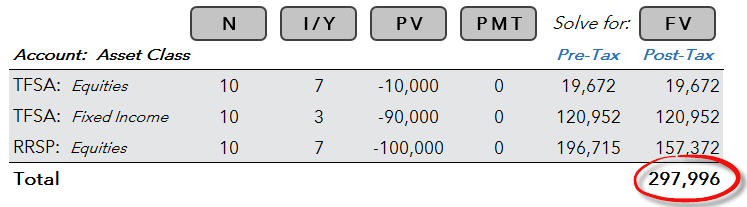

Option #3 (b): Equities in the RRSP first

Post-tax asset allocation: 50% equities / 50% fixed income

If the investor has instead decided to hold equities in the RRSP first, they would need to increase their pre-tax equity allocation to 55% to have a 50/50 post-tax asset allocation. However, at the end of the 10-year period, the post-tax portfolio value is again $297,996.

Option #3 (c): Same asset allocation across both accounts

Pre- and post-tax asset allocation: 50% equities / 50% fixed income

As before, having the same asset allocation across both account types results in the same ending post-tax portfolio value as Option #3 (a) and Option #3 (b): $297,996.

I’ve summarized the results in the table below.

Asset Location Results:

| Scenario | Asset Location Decision | Pre-Tax Asset Allocation | Post-Tax Asset Allocation | Post-Tax Portfolio Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Option #1 (a) | Equities in TFSA first | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income | $304,228 |

| Option #1 (b) | Equities in RRSP first | 60% equities / 40% fixed income | 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income | $304,228 |

| Option #1 (c) | Same asset allocation in each account | 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income | 55.56% equities / 44.44% fixed income | $304,228 |

| Option #2 (a) | Equities in RRSP first | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income | $291,764 |

| Option #2 (b) | Equities in TFSA first | 40% equities / 60% fixed income | 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income | $291,764 |

| Option #2 (c) | Same asset allocation in each account | 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income | 44.44% equities / 55.56% fixed income | $291,764 |

| Option #3 (a) | Equities in TFSA first | 45% equities / 55% fixed income | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | $297,996 |

| Option #3 (b) | Equities in RRSP first | 55% equities / 45% fixed income | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | $297,996 |

| Option #3 (c) | Same asset allocation in each account | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | 50% equities / 50% fixed income | $297,996 |

So where does all of this leave the discriminating investor? The greater goal is to adopt the best approach for you, that you’re most likely to stick with for real. Here are three choices to consider along a spectrum of possibilities, with my commentary about each, so you can decide for yourself.

Investor #3 (c): Don’t sweat the details.

If you hate math, taxes, and Excel calculators, holding the same asset allocation in both your TFSA and RRSP seems a fair compromise; don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. You’d find that approach in Option #3 (c), for example. You could simplify things even further by putting some self-rebalancing Vanguard Asset Allocation ETFs behind the wheel. Look, Ma, no hands!

Investor #1 (a): Don’t change anything.

If you ignore post-tax asset allocation, and you simply manage your portfolio to a pre-tax asset allocation (holding equities in the TFSA first, like in Option #1 (a)), your expected post-tax portfolio value will likely be higher than if you manage the portfolio to the same asset mix (but from a post-tax asset allocation perspective). A downside of this strategy is the slight drag from foreign withholding taxes levied on any foreign dividends received in your TFSA. However, if you weren’t planning to hold US-listed foreign equity ETFs in your RRSP anyway, this is a moot point.

Die-hard post-tax asset allocators will be unimpressed. They’ll insist that you’re taking more risk from a post-tax asset allocation perspective – and they’ll be right. But who really cares? For once, there’s a situation that allows you to take on more market risk in your portfolio, without actually feeling like you are. This could play to your favor. It’s not a free-lunch, but ignorance can be bliss.

Investor #3 (b): Complication? Bring it on.

If you had the ability to forecast tax rates like the precogs from Minority Report were able to predict crimes before they were committed, Option #3 (b) might be for you. Even in our world where free will still rules supreme, you might prefer to pursue best possible outcomes by finessing every lever available.

Managing to a post-tax asset mix would allow you to hold equities within your RRSP first. You could hold US-listed foreign equity ETFs in the RRSP, simultaneously reducing the withholding tax drag on foreign dividends. Don’t forget, you will need to increase your pre-tax equity allocation to implement this approach – and the higher your future effective tax rate, the higher your pre-tax equity allocation will have to be. That means you’d better be ready to buckle in and remain rational for the entire ride.

If you’re not much of a risk-taker, you could consider Option #3 (a), which would allow you to reduce your pre-tax exposure to equities. Compared to Option #3 (b), there would be an additional drag from foreign withholding taxes, as more foreign equities would be held in the TFSA.

Allocation, allocation, allocation

When you’re buying or selling your home, it’s all about location, or so the saying goes. For your investments, location matters, but I believe I’ve shown how asset allocations are really where it’s at. Better yet, factor in both considerations … to a degree. What degree? Again, while many may claim to have THE definitive answer for everyone, I’ve found individual preferences vary. Pick the “temperature” that works for you. Then go have a cold one to celebrate.

Hi there,

I’m a dual Canadian and American citizen, and am currently living in Canada. From what I can see, the Canadian TFSA is much more flexible than the American Roth IRA (https://creditcarrots.com/what-is-a-tax-free-savings-account/). Would you recommend maxing out my Canadian tax-sheltered/deferred options before moving on to US ones?

@Jamie – I would recommend that you speak with a cross-border tax specialist. TFSAs are generally not advisable for dual Canadian-U.S. citizens.

Hi Justin,

Currently my TFSA and RRSP are both worth about the same in after-tax dollars and due to most of my RRSP contribution room going to a RPP I can reasonable expect them to stay about the same. If I’m using the model portfolio with 100% equities and I’m comfortable with Norbert’s Gambit, does it make sense to hold:

In RRSP: ITOT (57%) IEFA (31%), IEMG (12%)

In TFSA: VCM (66%) ITOT (19%), IEFA (11%), IEMG (4%)

Just in an effort to minimize foreign withholding tax?

The savings aren’t huge (I think I get around $130/year on a $200k portfolio, but it’s also not really any more complex, so I don’t see any drawbacks.

@Steve: If you’ve decided to manage your portfolio from an after-tax perspective, holding U.S.-listed foreign equity ETFs in your RRSP first would be more tax-efficient (from a foreign withholding tax and product cost perspective).

There’s no overall tax/cost savings advantage in a TFSA though. If you just held 66% VCN + 34% XAW, the total cost would be 0.23% per year. If you held 66% VCN, 19% ITOT, 11% IEFA and 4% IEMG, the total cost would also be 0.23% (I used the CPM Foreign Withholding Tax Calculator to estimate these costs):

https://canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/calculators/

Hi Justin, thanks a lot for these blog posts and model ETFs! Your and Dan Bortolotti’s insights are both extremely helpful!

Reading through this post, you’d made the assumption that the time horizon for both the TFSA and RRSP are the same – 10 years, and therefore you’re adjusting asset allocation and asset location to maximize returns at that fixed horizon. For someone who’s younger with a stable career – i.e., RRSP withdrawals are 25+ years away, then would it not make more sense to adjust risk ratios accordingly? Such as, setting your TFSA ratio separately in the context of when I could foresee myself dipping into my TFSA savings (i.e., kids, house, etc – or maybe 50/50 or 60/40), while keeping my RRSP ratio at 100% equities, and not lowering the risk of my RRSP investments until 5-10 years or less from retirement?

I’ve heard the rule of thumb many times that RRSP should house the fixed income portion of the portfolio, but I haven’t seen any insight about different time horizons for each account and how that rule of thumb would then be adjusted.

Thanks again for all the great work you’ve done to educate Canadians!

@Simon Edwards: “Bucketing” accounts for upcoming expenses doesn’t really have to do with this blog post. I’ve assumed that the investor is using all assets for retirement purposes (i.e. long term).

If you need funds in the short-term (i.e. for a home down payment), you should not be investing in equities in the TFSA in the first place (so I would exclude the account from any long term portfolio asset allocation).

Hi Justin,

First, thanks a lot for the blog. Love it.

I’ve read this series of posts and I am really struggling to get my head around this idea of targeting “post tax” allocation as the right objective. I was hoping you could help me rationalize.

First, the calculation rests on knowing what one’s RRSP withdrawal tax rate will be. If you are 30, it seems to me as though this is very much a guess. 10%? 20%? 40%? Heck maybe governments get out of hand and it’s 80%. 2048 is a long way off. :) Far away from retirement/consumption, it seems to me as though the confidence interval of your estimation on this critical number can’t possibly be much sharper than +/-20%. So trying to plan based on that – why bother? Why not just keep the math more simple and work based on pre-tax allocation?

Later, closer to retirement, perhaps you can gauge this number with more confidence. But then, at that point, we do not really care anymore, do we? I get the theoretical argument, but it seems to me that from a practical standpoint, it also makes things more complicated, not less. With trading costs being so low, one can always rebalance after any withdrawal (for example, in the case that an RRSP is being drawn down first, before other accounts). It seems to me this would be preferable / lower cost than holding equal allocations in every account for years preceding.

Anyway, I guess the crux of my argument is, while targeting post-tax allocation may theoretically & mathematically be the “correct” way to go about this, don’t (a) the lack of knowledge of future tax rates and (b) real-world factors like almost-zero trading costs these days make this kind of an “illusion of precision” exercise?

Cheers

Dan

@Dan: I think you’ve already figured out the point of my post – stop sweating the asset location decision ;)

Justin, thank you for such intersting insights! Correct me if I am wrong, but to my mind the article seems to ignore one rather important nuance. It makes an assumption that the 20% tax does not depend on the location choice when it normally does. As far as I am aware, when one retires there is an enforced minimum schedule of consuming the collected rrsp which potentially may increase ones tax margin if he ended up accumulating more in rrsp, while on tfsa there isn’t any enforcement. Intuitively it suggests me equities in tfsa makes the endgame more flexible. Could you comment on it?

@td: The analysis assumes that the investor knows with certainty their effective tax rate in retirement (as you can imagine, this is a big assumption). It also does not assume that more Old Age Security (OAS) may be clawed-back due to the higher forced minimum RRIF withdrawals in retirement (which can also be a significant factor).

This is all the more reason to choose an asset location strategy that you are comfortable with, instead of obsessing over optimizing the portfolio.

Justin would you recommend I invest in an RRSP after my TFSA is maxed out, I have a DB pension with omers and make 100000 a year, plus my wife has a DB pension with the federal government.

@Nick: You should speak with a fee-only financial planner to determine which option makes the most sense for your family’s particular situation.

Hi Justin,

Thank you for your post. I was wondering if you could consider carrying this comparison on to include taxable accounts. I am about to start contributing to my taxable account.

I’m using your model portfolio and I decided that it would be best to have a large portion of my VCN holdings to be located in my taxable account.

I will be drawing from my RRSP first in retirement so I decided I would keep a balanced portfolio there, with all of the bonds and a balance of the other ETFs. This leaves an excess of VCN that I can put in my taxable account.

I have created an excel spreadsheet for all of this but its actually pretty complicated and confusing.

Any advice?

@Matt: I’ll be following up with two additional posts: TFSAs vs. Taxable Accounts and RRSPs vs. Taxable Accounts – which will hopefully provide some food for thought (although the main concepts are more-or-less the same as in this blog post.

I like it – I mean, not just your post, but that as probably the most common approach is to ignore post tax calculations (because that’s too complicated) and hold bonds in your RRSP and equities elsewhere (because that’s the usual advice related to tax efficiency), that results in investors taking more risk than they realize, resulting in a higher expected return, by using the government’s money in the RRSP to help smooth the ride. A nice behavioural benefit of the RRSP.

@Grant: I definitely find more behavioural appeal to the traditional or naïve approaches to asset location/allocation (as opposed to the process of trying to optimize what can’t really be optimized). Either way, it makes for good discussion and debate :)

Thanks for writing about this, Justin. I’ve been wrestling with this one over the past year as my portfolio has gotten big enough to necessitate a nontrivial taxable account.

I know that adding portfolio rebalancing to these analyses complicates things, but in my own ceaseless spreadsheeting, rebalancing really does seem to make a big difference in the outcome. Particularly, yearly rebalancing reduces the effect of strategic asset location. Sometimes significantly.

You wrote: “Die-hard post-tax asset allocators will be unimpressed. They’ll insist that you’re taking more risk from a post-tax asset allocation perspective – and they’ll be right. But who really cares? For once, there’s a situation that allows you to take on more market risk in your portfolio, without actually feeling like you are. This could play to your favor.”

But it can go the other way too. For example I have mostly GICs in my taxable account such that my pre-tax allocation is 63/37 and my post-tax allocation is 60/40. So from a post-tax perspective I’m actually taking *less* risk.

Amusingly, I find myself tempted into using the margins offered by the ambiguity of pre vs post tax allocation to exercise a bit of market timing. If my post-tax allocation has me a bit more in equities than my 60% target and my irrational self thinks we’re staying in a bull market, I’m less fussed if equities are weighted a couple extra percent after taxes. Whereas if my gut tells me we’re headed into a correction, I’d be more strict, maybe even rebalancing my post-tax equities a couple percent under my target if the math works out easier.

I recognize it’s a pointless psychological game, but I allow it because it’s not like asset allocation is an exact science to begin with. It’s my version of scratch money to play the stock market. :)

@Jason: If you’re comparing an RRSP + taxable account where you hold equities in your RRSP account first (with a pre-tax allocation of 63/37 and a post-tax allocation of 60/40) with an RRSP + taxable account where you hold equities in your taxable account first (with a pre-tax allocation of 63/37), your post-tax allocation will be more aggressive than 60/40 (as the fixed income amount in your RRSP is worth less after tax), so your ending portfolio is expected to be higher in this scenario (as you took more post-tax risk).