Among the most common questions I receive from blog readers is: “How do I tax-efficiently manage an ETF portfolio across various account types?” This question relates to asset location – or which asset classes should end up in which accounts. This is not to be confused with asset allocation, which is how much of your portfolio to allocate to each asset class.

If that’s still a little confusing, think of the assets in your portfolio as being like the hours in your day. You may allocate eight hours each to working, playing and resting. You’ll also locate each hour in a place most appropriate for the activity – such as a dark, quiet room when it’s time to sleep. Similarly, you may allocate 40% of your assets to fixed income and 60% to equity, but you’ll locate these holdings where you’ll get the most tax-efficient bang for the buck.

Big picture, that means you want to consider the tax efficiency of each type of holding, based on its potentially taxable annual interest or dividends, as well as its potentially taxable eventual capital growth through the years. (At least we hope your holdings grow!) You then locate each holding where both types of tax ramifications are expected to cause the least overall damage done.

So how does that work?

First, a few ground rules. In the scenarios that follow, I’ll assume a 40% fixed income/60% equity asset allocation. Since most investors are managing a similarly balanced/rebalanced portfolio, this practical model strikes me as a happy medium between ignoring the potential tax-saving benefits of asset location, versus taking the calculations to an extreme.

If you really wanted to sharpen your pencil, some might suggest using the less-traditional, but more complex after-tax approach for calculating optimal asset locations. Since asset location is always a best-estimate effort (with THE best answer only available in hindsight), it seems to me that the law of diminishing returns begins to apply.

Let’s get started!

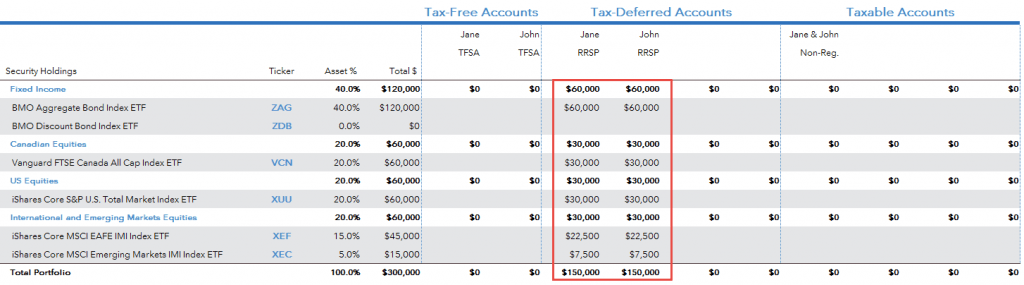

Scenario 1: All assets in RRSP accounts

This is the most basic situation. Obviously, if you only have one type of location in which to invest your assets, your choice of location is pretty easy. It’s like living in a one-room house. The only way to make the portfolio slightly more tax-efficient is to swap out the Canadian-listed foreign equity ETFs for their US-listed counterparts (using Norbert’s gambit to convert your loonies to dollars).

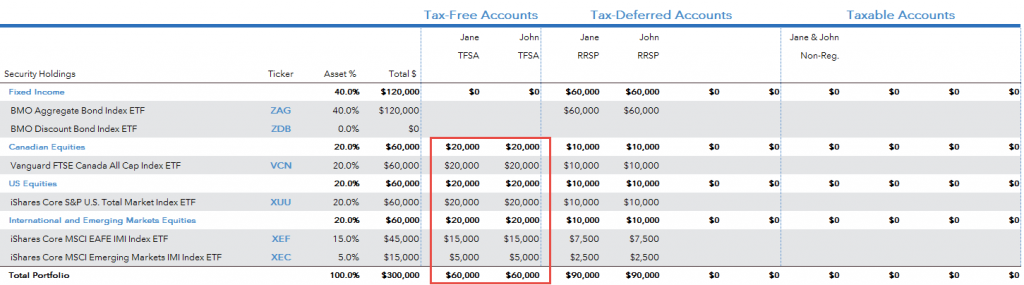

Scenario 2: Assets are split between TFSA and RRSP accounts

In this situation, you and your spouse have assets in both TFSA and RRSP accounts. As all growth and dividends that accumulate in a TFSA account are never taxed (even upon withdrawal), investments with the highest expected returns should be held here first.

That makes equities the obvious choice for the TFSA account. Unfortunately, we have no idea which equity region will outperform moving forward. As a personal preference, I choose to hold Canadian, U.S., and international/emerging markets equities evenly, to mitigate my regret if I otherwise managed to choose the worst outcome. Feel free to adjust this allocation if you would rather roll the dice.

Don’t bother holding US-listed foreign equity ETFs in your TFSA accounts – this does nothing to mitigate foreign withholding taxes.

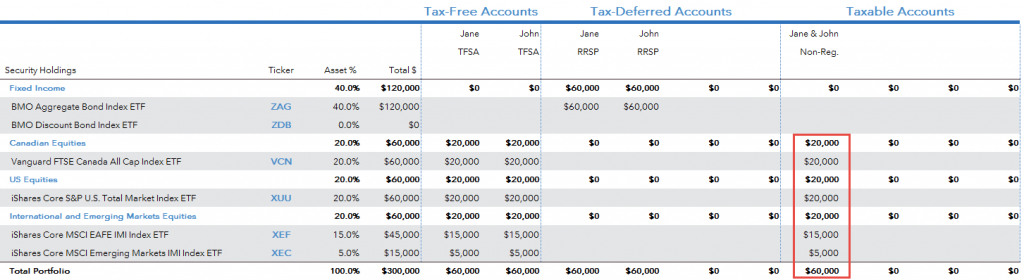

Scenario 3: All equities fit into TFSA and taxable accounts

Once you’ve maxed out your TFSAs with equities, your taxable accounts are usually the next best location if you have more equities (since only 50% of capital gains are taxable there). You may also stumble across tax-loss selling opportunities in your taxable accounts, which could help you defer future capital gains taxes when rebalancing your portfolio.

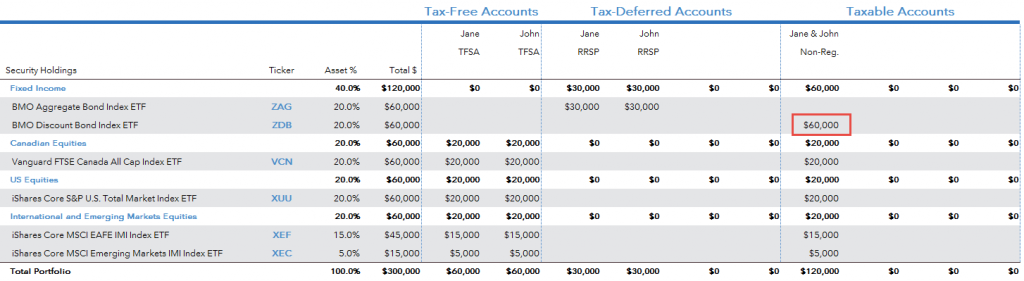

Scenario 4: Fixed income has spilled over into the taxable account

Your portfolio is looking great and you’re on the right track. Just don’t blow it by holding tax-inefficient fixed income products in your taxable account. As I’ve written about in the past, most bond ETFs are not ideal candidates for taxable investing (due to the higher coupon payments of the underlying bonds). The BMO Discount Bond Index ETF (ZDB) attempts to mitigate this issue by investing in lower coupon bonds. As you can see in the chart below, the taxes paid on a $10,000 taxable investment were substantially less for ZDB vs. the BMO Aggregate Bond Index ETF (ZAG).

2016 taxes payable on a $10,000 investment (Ontario taxpayer in the top marginal tax bracket)

| Exchange-Traded Fund | Asset Class | Total Taxes Paid (2016) |

|---|---|---|

| BMO Aggregate Bond Index ETF (ZAG) | Canadian Bonds | $150 |

| BMO Discount Bond Index ETF (ZDB) | Canadian Bonds | $103 |

Sources: CDS Innovations Inc. Tax Breakdown Service, BMO ETFs

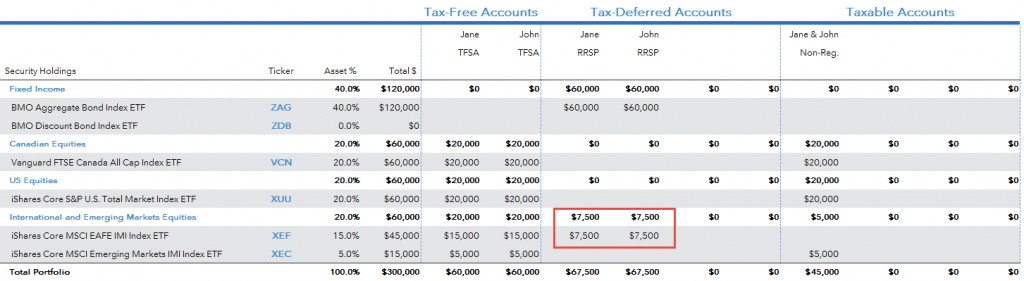

Scenario 5: RRSP accounts must still hold some equities

What if you can’t fit all of your equities into your TFSA and taxable accounts? Generally, if you must hold some equities in your RRSP accounts, opt for international equities. With their fully taxable and juicy dividend yield of around 3%, the taxes payable each year will take their toll. In the chart below, I’ve shown the taxes paid by an Ontario resident in the top tax bracket during the 2016 tax year for a $10,000 investment in each equity ETF. As you can see, holding international equities resulted in higher taxes payable during the year than any of the other equity regions.

This is also a good example of when it makes sense to build a 5-ETF rather than a 3-ETF portfolio. Holding a global equity ETF (such as the iShares Core MSCI All Country World ex Canada Index ETF (XAW)) would not allow you to isolate the less-tax-efficient international equities, so you could locate them within your RRSP account. Breaking up the ETF into its underlying U.S., international and emerging markets components provides more flexibility in this situation.

Depending on where you live in Canada (and your actual tax rate), prioritizing the asset location order for remaining equity asset classes could differ from the results below. Next week, we’ll take a closer look at that.

2016 taxes payable on a $10,000 investment (Ontario taxpayer in the top marginal tax bracket)

| Exchange-Traded Fund | Asset Class | Total Taxes Paid (2016) |

|---|---|---|

| Vanguard FTSE Canada All Cap Index ETF (VCN) | Canadian Equities | $109 |

| iShares Core S&P U.S. Total Market Index ETF (XUU) | U.S. Equities | $103 |

| iShares Core MSCI EAFE IMI Index ETF (XEF) | International Equities | $146 |

| iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets IMI Index ETF (XEC) | Emerging Markets Equities | $112 |

Sources: CDS Innovations Inc. Tax Breakdown Service, BlackRock Canada, Vanguard Canada

Hi Justin – I’m in the process of planning the allocation of my retirement portfolio after a non-reg cash injection and seeking location advice. I fully realize there is no perfect solution given all variables involved, but want to ensure I’m not missing anything significant. Registered accounts are maxed out, and reside in Ontario.

Target allocation is 20% Cdn/22% US/18% Intl, 5% REIT, 35% Cdn bond.

Current location by asset %: TFSA 1 (6.39%: VCN), TFSA 2 (7.02%: VRE), RRSP 1 (40.49%: VTI, VCN), RRSP 2 (18.69%: VXUS, VAB), LIRA (14.51%: VAB), INV 1 (9.27%: VCN), INV 2 (3.62%: VCN)

Plan location by asset %: TFSA 1 (3.75%: XEF/XEC), TFSA 2 (4.12%: VRE), RRSP 1 (25.25%: IEMG, VAB), RRSP 2 (10.96%: VAB), LIRA (8.5%: VAB), INV 1 (44.89%: VCN, VUN), INV 2 (2.52%: XEC)

Other considerations:

– VTI instead of XUU in the investment account. Not sure the pros outweigh the cons, though comfortable converting

– All FI in investment account using ZDB, keeping US/Intl sheltered. Does this tip the scales enough to consider vs above?

– Reducing account concentration (e.g. not optimal to only carry VRE in TFSA 2 given we want TFSA with good growth potential – instead spread out US/Intl and even Cdn across TFSAs?). Prefer to limit duplication but not at the expense of growth risk or tax paid

Hi Justin and thanks for all your articles, both yourself and CCP have helped me tremendously!

I see a lot of articles like this one about asset location, but I haven’t found any discussing the case where someone reaches financial independence at a young age. Suppose in that case, you are withdrawing money from your RRSP and Taxable account each year, planning to deplete them both before you get CPP/OAS. Is there a way to tell in that case what asset location to lean towards?

Thanks!

@Dave Crausen: If you’re planning to deplete all of your portfolio assets by age 60-70, I’m not sure if you’d be classified as “financially independent” (unless there is something I’m missing). Either way, this is a very specific situation that you should seek professional advice on.

Hi Justin

Thank you for all the informative articles and tools .

And your easy to follow blog.

My question is at the Portfolio Manager ;

Scenario 3: All equities fit into TFSA and taxable accounts.

This scenario would be a good fit for our situation and will start to implement

into our accounts.

Question do you have a excel tool that could show minimum withdrawal rates from RIF and where this income is best placed (re-balance time)? If income is not needed?

My wife’s RIF min. withdrawals start this year. Have to withdraw by Dec 20,2018.

Can this be incorporated into your Re balance excel spread sheet?

@Wayne O: If your bond ETFs (such as ZAG) are in your wife’s RRIF account, you could sell enough shares of it to make her minimum RRIF payment to her taxable account. If she doesn’t require the cash, she could reinvest the RRIF proceeds into a tax-efficient bond ETF (like ZDB) or top-up your equities if they are below their target allocations.

Hi Justin,

Great article. I have a question regarding splitting/location between RRSP & RRIF (35 / 65 split). Would it make sense (if possible) to locate my assets across these accounts so that all of my US-listed ETF’s are purchased in only one of these two accounts in order to only have to do Norbert’s Gambit once? I.e. As per this article, I could fill my TFSA with equities, then put the bonds into the RRSP (and any leftover bonds into RRIF) and finally the remaining equities into the RRIF, thus having only US-listed equities in the RRIF. Or would it be best to split the bonds/remaining equities proportionally across the RRSP & RRIF thus doing a Norbert’s Gambit for both the RRSP & RRIF?

I hope this makes sense, any advice would be greatly appreciated.

Thanks.

@Kyle: Holding the US-listed ETFs in a single registered account would be acceptable (there’s no need to split the allocation up between registered accounts).

Why do you recommend not holding XEF in the taxable account in scenario 5?

“Generally, if you must hold some equities in your RRSP accounts, opt for international equities. With their fully taxable and juicy dividend yield of around 3%, the taxes payable each year will take their toll.”

I see that annual taxes payable in the taxable account are higher for XEF than others per your chart.. but you get FWT credits in the taxable account, and you eventually have to pay RRSP taxes on the total when you withdraw. Does growth on re-invested (tax deferred) dividends really overcome the FWT benefit over 20 years?

@Kristen: The annual taxes payable figure for XEF already assumes that all foreign withholding taxes paid have been recovered (I’ve used the gross foreign income figures from the CDS.ca website). Remember that foreign withholding tax implications shouldn’t be viewed in isolation (higher dividend yields can create an additional tax drag that is more than the foreign withholding tax drag).

I ran some figures to see if holding another asset class in the RRSP account first rather than international equities would lead to a higher after-tax return after 20 years, and it didn’t.

Assumptions:

– Starting portfolio has $100,000 in an RRSP account and $100,000 in a taxable account

– One asset class is held in the RRSP account and one asset class is held in the taxable account

– Portfolio is not rebalanced

– Gross Dividend Yields – 2.92% for international equities, 1.90% for US equities, 2.77% for Canadian equities

– Foreign Withholding Tax Drag in RRSP account – 0.25% for international equities and 0.28% for US equities

– MERs – 0.22% for international equities, 0.07% for US equities, 0.06% for Canadian equities

– Tax Rates – 53.53% for foreign dividends and the taxable portion of capital gains and 39.34% for Canadian eligible dividends (Ontario top rates)

– Expected Return – 7% for each (this includes the gross dividend figures)

– Investment Period – 20 years (after which all gains are realized and the RRSP account is deregistered)

Results:

1. International equities in RRSP and US equities in taxable = $18,676 benefit after 20 years

2. International equities in RRSP and Canadian equities in taxable = $13,578 benefit after 20 years

Please keep in mind that these results can easily change, depending on your specific tax situation.

@Justin: I’m curious why you used a 0.28% foreign withholding tax drag for US equities in the RRSP account. This suggests you modeled a portfolio with a Canadian-listed US equities ETF in the RRSP account, rather than a US-listed ETF where foreign withholding taxes don’t apply? That would certainly make it much less attractive to hold the US equities in the RRSP account. Did I misunderstand?

Cheers!

@Jason: I could have assumed that a US-listed US equity ETF was held in the RRSP (with no foreign withholding tax implications), but this wouldn’t have changed the conclusion (that international equities are better held in an RRSP account rather than a taxable account, relative to US equities).

Hello again Justin,

to summarize your examples, if you are in a position due to asset availability to ”one-class” an account because all classes of asset spill over the taxable account anyway and if I read you correctly, TFSA would be pure equity (one third US, one third CA, one third intl/emerg); RRSP would be pure bond and taxable a mix of asset class to fill the ”void”? Correct me if I’m wrong. And thanks in advance.

@Pete S: That’s correct! (and also ensure that you invest in a tax-efficient fixed income ETF in your taxable account)

Sorry but I disagree with most of this. You knew I would post didn’t you?

1) You never define or measure what you mean by ‘tax savings’. I propose that the ‘benefit’ from using any tax shelter should be the difference in $ outcomes vis a vis a Taxable account. But it sounds like you are measuring the $tax paid/not in year one only. Probably using a metric that divided that $tax by the $invested.

2) That means you are ignoring the impact of TIME. Time allows the income-sheltering benefit of tax shelters to compound. Time allows assets with high-returns / low$tax-in-yr1 (ie stocks) to accumulate more $benefits than assets with low-return / high$tax-in-yr1 (ie treasury debt).

3) You say it is obvious that TFSA are better for holding high-return stocks, than RRSP, because profits in TFSA are not taxed on withdrawal. That makes the false presumption that RRSP profits ARE taxed on withdrawal. Yet when cont/draw tax rates don’t change the $outcomes are equal, so it is ‘obvious’ that RRSP’s shelter profits permanently exactly the same.

4) When choosing whether to fund an RRSP vs TFSA most people only choose the RRSP when they predict they will face lower tax rates on withdrawal. That will earn them a Bonus = the $draw * (reduction in % tax). The AL choice should attempt to maximize this Bonus. The higher the asset’s rate of return, the larger the account will become, which means the $draw will be larger and the $Bonus will be larger. That means that higher-return assets should be prioritized in the RRSP (vs the TFSA), not the other way around that you propose. That would only be subject to a check that the larger account would not result in required RRIF draws at a higher tax rate – which is unlikely.

5) If in your scenario both RRSP and TFSA are being used because the TFSA room was used up in preference, because a higher tax rate at RRSP withdrawal was expected …….. then an RRSP Penalty would be expected, and you minimize the Penalty by putting lower return assets in the RRSP so that the $draw will be smaller. It all depends on whether you expect a Bonus or Penalty from a change in tax rates.

6) Your idea that stocks should be kicked out of tax shelters before debt when they run out of room …. seems to come from your metric for tax efficiency that ignores time. Instead compare $outcomes. EG

Second tax bracket

Treasury debt with 1.5% return made up of 3% interest taxed at 30.8% and 1.5% capital loss taxed at 15.4%. That makes for an effective tax rate of 46.2%

vs

Canadian stock with 7% return made up of 3% dividends taxed at 11.3% and 4% capital gains deferred 20 years taxed at 11.3%. That makes for an effective tax rate of 11.3%

After 20 years the accumulating benefits from bond in the tax shelter is only $2,602, while the tax sheltering from stocks would be $7,386. It is the growth rate that matters over time. Stocks are better placed inside tax shelters than bonds.

@Chris: I definitely don’t disagree with most of your comments if the investor is calculating their asset allocation from an after-tax basis. I think you would agree that this is not how the majority of investors are managing their investments, so your comments can be very misleading if they miss this point (I speak with investors that have read your material and hold equities in their RRSP accounts first, but are managing a traditional asset allocation).

Sorry, I did not understand your ..”calculating their AA from an After-tax basis” or “managing their investments”. I was posting regarding AL Asset Location without any presumptions or inputs regarding AA. The calculations of $benefits is done on an individual asset basis, and won’t change if other assets are held or held in different %.

Are you saying that you (will you speak for CCP?) are refuting the math and logic of my linked (under my posting name) AL material just because you don’t agree with the AA methodology presented in the material directly above that? Is your impression somehow that my AL material is related to Reichenstein’s ideas that you link to at the very top?

Both ideas are wrong. I disagree with Reichenstein entirely. His ideas on AL do indeed integrate with AA because he abandons the AL objective of ‘maximizing tax savings’ for his objective of ‘an optimal MVO’ (mean variance optimization) which is how ‘professionals’ determine AA percentages instead of using rules of thumb. In my SSRN paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2317970) I include at the end a separate section disputing his objective, and disputing the claim that it reduces taxes (which he has never even tried to prove). Please do not ever link me to his ideas.

You are correct that I tell people that simple AA percentages won’t work if they AL across multiple accounts that include an RRSP (because some % of the RRSP account is not YOUR money, it belongs to the government who just goes along for the ride). BUT their choice if/how they make the necessary adjustments to their AA has absolutely nothing to do with their AL decision (which assets get the most $benefits from tax shelters).

The $benefits from RRSPs (what AL is trying to maximize) are mainly the sum of two factors – neither of which considers AA, both of which look at assets individually without regard to any other. both of which depend on only (i) tax rates, (ii) rates of return (of the asset being considered only), and (iii) time.

The first factor is the the difference between the Future Value of the after-tax $savings compounded at tax-free rates of return vs. compounded at after-tax rates of return. This always equals the same $benefit from a TFSA. The second possible bonus/penalty is the $withdrawn multiplied by (tax % at contribution less tax % at withdrawal). You can see from that math that however you AA with any other assets has no bearing. How you calculate their AA percentages has no bearing. Just one asset’s benefit is measured in isolation. .

@Chris: First off, Reichenstein has a decent example of the concept of after-tax asset allocation in his article, which is why I provided a link. It was not meant to be a comparison to your paper. This is my blog, and I can provide links to whichever articles I choose – they do not have to be pre-approved by Chris Reid.

Secondly, no one is refuting your math. I am simply saying that in my opinion, the concepts are not very helpful for DIY investors who are trying to manage a simple ETF portfolio. I would encourage you to create a similar blog post that incorporates your own math, but provides some practical concrete examples on how to construct and manage an ETF portfolio tax-efficiently based on your work.

I should have read the comments! I was just about to put up a blog post on my realization as to why Justin keeps getting “bonds in RRSP” as optimal when I get “equities should be sheltered when expected bond returns are low”, and it’s because of after-tax allocation. I would have been months further ahead as you guys were already deep in the weeds about this last summer!

Anyway, I see that there are two sides to the debate and there isn’t an easy, universal answer. However, I think I come down on the tax-adjusted asset allocation when trying to optimize (even if only approximately). To give a quick example of why, I’d suggest changing your return expectation for bonds to 0 in your Scenario #3. If I’ve approximated your methods right, you’ll still find that bonds go in the RRSP for an “optimal” 60:40 portfolio, which makes no intuitive sense: with 0 return there’s zero tax to shelter. It also explains why bonds go in an RRSP but not a TFSA (as in scenario 4) with these methods.

Of course, the debate on whether to adjust for taxes or not gets into what asset allocation is for, complexity, etc. etc.

When it comes to asset location, maximizing the absolute amount of tax saved is my priority. Sometimes people focus on the tax savings relative to the return of an investment. For example, assume 50% tax on fixed income and ordinary income, 25% on cap gains, and 35% on Canadian dividends. If returns are similar for each asset class, then saving tax on fixed income is the priority. But if returns are significantly greater for stocks, then the absolute amount of tax saved may be greatest by focusing on stocks. For a long term investor, stocks returns will most likely be eventually sufficiently greater than fixed income such that the tax efficiency priority should be stocks.

Another point when it comes to asset location is that your present balances in each account are not what is most important. What’s most important is what income you will have after all taxes are paid. You may have an impressive RRSP, but if it gets taxed at 50% on withdrawal, it will be less impressive. To a lesser extent, this also applies to taxable accounts, where unrealized cap gains will eventually be realized. So once again for a long term investor, that tends to means stocks first in TFSA then taxable then RRSP.

Within stock subasset classes, what should determine asset location? Each subasset class will likely have similar long term return. This assumes a couch potato investing strategy. Emerging markets might/might not have a greater long term return, but that’s debatable. If returns are similar, what’s important then is how much of the return is cap gains and how much is dividends. It’s also important that Canadian stock dividends are taxed less than other stocks. Both have to be taken into account. EAFE dividends are higher than Canadian dividends and are taxed more. So EAFE dividends should have a higher priority than Canadian dividends. US dividends are taxed more than Canadian dividends, but US dividends are lower than Canadian dividends. So the absolute amount of tax saved is slightly greater by prioritizing Canadian stocks over US stocks.. When it comes to tax efficiency, the number one priority is EAFE stocks then emerging market stocks then Canadian stocks then US stocks.

A complication with RRSPs and TFSAs is that your tax rate at the time of contribution and also withdrawal are relevant. For example, if your tax rate at the time of contributing to your RRSP is 54% but is 0% at withdrawal, that’s relevant. Similarly, if your tax rate at the time of contributing to your TFSA is 0% but at withdrawal is 54%, that’s relevant. That’s one small advantage of being a higher net worth investor :-). You can probably make an assumption that the higher tax rates are what’s most relevant to you at the time of contribution and withdrawal.

Also, how long you are investing for is relevant. A 50% tax on RRSP withdrawal may at first glance suggest that stocks go in taxable over an RRSP. But assume you contribute at age 18 and withdraw at age 71. The tax free growth of RRSPs might overcome that 50% withdrawal tax handicap.

However, if you worry about whether stocks should go in taxable vs. RRSP vs. TFSA, you probably have a portfolio of moderate size at least. If you have a portfolio of such size, that means you’re likely an older investor. And if you’re an older investor, your time horizon until RRSP withdrawal will be shorter. For such an investor, the 50% withdrawal tax may be more important than the tax free growth of an RRSP.

For corporate accounts, nonCanadian dividends have an effective tax rate greater than in an open noncorporate account, whereas Canadian (eligible) dividends have the same tax rate. So the priority in corporate accounts should be Canadian stocks.

In an RRSP, US investments in US domiciled vehicles won’t be exposed to withholding tax. But in a TFSA, you’re exposed to the tax and can’t recover it. Still, the difference is small enough that it shouldn’t change your plan.

This all assumes that tax efficiency is paramount. But for some, rebalancing is important. Rebalancing is primarily to manage risk. It’s reasonable to put a greater priority on risk management than tax efficiency. In such cases, it makes more sense to put fixed income in taxable accounts and stocks in registered. With such an asset location, you can rebalance with the greatest tax efficiency.

For others, liquidity may be important. In such cases, fixed income should go in taxable accounts, as that will maximize tax efficiency.

Asset location is not straightforward :-).

Someone in this thread has mentioned OAS clawback. When it comes to OAS clawback, then Canadian dividends become less tax efficient, and the forced income of an RRSP can become an issue. I’m hoping to be in a higher marginal tax rate when I’m retired, so that won’t be an issue :-).

I’d like to thank Justin and others for their ideas, as my two posts are completely derivative.

I’m wondering if you’re confusing OAS clawback with GIS, the guaranteed income supplement for low income retirees. OAS clawback is very much an issue for those in higher tax brackets!

@Park: You’ve definitely been busy ;) Many of your points are valid – I’ll be discussing the equity region asset location order in taxable accounts next week, where there should be even more numbers for you to digest :)

Justin,

Thank you for writing this very useful and clearly articulated post.

If the Federal government proceeds with its proposal to limit CCPC to earn passive income, will the above asset location recommendations change? I understand that the answer to this question is currently uncertain, and that the proposed changes have not been finalized. Will you be writing an update once the small business tax laws have been changed?

@John: The asset location scenarios likely won’t change. I would assume that most business owners would just start investing in personal non-registered accounts (instead of corporate accounts). There may be some additional opportunities for asset location decisions between personal and corporate non-registered accounts, which I will be discussing at a later time.

Hello Justin,

For those with defined benefit pension plans and limited RRSP room does it make the most sense to follow scenario #5? I’m still fairly young in my investing career so am following an allocation of 80:20 equities to bonds. I remember reading an article by your colleague Mr. Bortolotti in Moneysense where he mentioned that if an RRSP gets too big there are issues with OAS clawbacks upon retirement.

Also, if one were to hold $10,000 of XAW in an unregistered account do you have an estimate of the total taxes paid on the yield?

Thank you so much for another excellent post and I’m looking forward to your next article.

PS A future post on drawing down investments upon retirement would be extremely helpful! I’ve always been kinda curious how things would roll in terms of drawing down non-reg investments first vs RRSP vs TFSA etc.

@Paul: If your portfolio is allocated 80% equities, 20% bonds (and you have RRSP, TFSA, and taxable accounts), scenario #5 would allocate your equities to the TFSA account first, the taxable account second, and the RRSP account third (with lower-yielding bonds prioritizing your RRSP account). International equities would be the first equity asset class to hold in your RRSP (if necessary) – the next equity asset class would likely depend on the province/territory you live in and your tax rate.

I don’t have an estimate for XAW’s tax implications during 2016, but if I have some time today, I’ll put one together.

In order to create a tax-efficient withdrawal strategy in retirement, an ongoing financial plan would be necessary. I generally recommend investors seek out a competent advisor when they’re in this situation.

@Paul: In 2016, an Ontario taxpayer in the highest marginal tax bracket would have paid $110 in taxes on a $10,000 holding of XAW.

Hi Justin,

Thank you so much for this very helpful post!

This post goes along the same lines as your white paper ‘Asset Location for Taxable Investors’

But, in previous posts, in the comment section in response to my questions, you favored putting international equities in the RRSP first, not necessarily fixed income. Instead, fixed income would go in taxable account ( in my case corporate account) because of the existence of tax efficient etfs such as ZDB.

For example, see your John Smith Portfolio and comments section of the following post:

https://canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/perfecting-the-perfect-portfolio-part-ii/

Has something changed? Or is it an also acceptable way to locate assets and only time will tell which one was best?

Right now, my RRSP is 50% fixed income and 50% international equities, because I wasn’t sure which way to go…

Thx

D

@D: Thank you for pointing out the discrepancy (I’ve taken down that example, as it doesn’t flow very well with these updated ones).

Your comment “Only time will tell which is best”, is likely the most accurate comment about asset location. If you focus on the annual tax-efficiency of the asset class, you may decide to hold tax-efficient bond ETFs in a taxable account instead of international equities. If you also consider the expected growth of each asset class, this may lead you to hold bonds in the RRSP and international equities in the taxable account. If you calculate your overall asset allocation from an after-tax point of view, this may lead you to hold all equities in your RRSP account and tax-efficient bonds in your taxable account.

Corporate accounts throw another wrinkle into the mix, as foreign dividends do not integrate well as they are passed along from the corporation to the shareholder (I’m going to be writing more on this topic).

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with how you’ve set-up your portfolio. If you decide in the future to move your international equities to your corporate account instead, this is an easy fix without significant tax implications (i.e. sell international equities in the RRSP, sell bonds in the taxable, buy international equities in the taxable, buy bonds in the RRSP).

Super useful.

But what does “What if you can’t fit all of your equities into your TFSA and taxable accounts?” mean in practice? Obviously a taxable account doesn’t have a contribution limit, the way a registered one does, so why wouldn’t any amount of equities fit?

MStep: In scenario #5, the total portfolio is worth $300,000, and the target equity asset mix is 60% (which means that $180,000 of the portfolio should be allocated to equities). The TFSAs are worth $120,000, the RRSPs are worth $135,000, and the taxable account is worth $45,000.

Equities are allocated to the TFSA account first (using up $120,000 of the $180,000 equity allocation – this leaves $60,000 to go). Equities are then purchased in the taxable account, which uses up $45,000 of the remaining $60,000 equity allocation). The only accounts left to buy equities in are the RRSP accounts, so the remaining $15,000 equity allocation is purchased there).

You recommend holding only*** Canadian listed equities in TFSA?

Justin, I just wanted to say thank you for this great update! I read the update several times as I find there is a lot of pertinent information for young investors like me. I’d be grateful if you can please elaborate where you wrote in scenario 2: “Don’t bother holding US-listed foreign equity ETFs in your TFSA accounts – this does nothing to mitigate foreign withholding taxes.” You recommend holding on Canadian listed equities in TFSA? Thanks again for this great update.

@Maximus: I’m glad you enjoyed the update :)

Holding US-listed foreign equity ETFs in a TFSA account does not avoid the 15% US withholding tax rate on dividends, making it very similar to the tax implications of holding Canadian-listed foreign equity ETFs in a TFSA account (the tax drag would actually be slightly worse for US-listed international equity ETFs). The only benefit would be from reduced product fees on the US-listed ETFs, but there would also be a cost to the currency conversion (even when using Norbert’s gambit).

https://www.pwlcapital.com/pwl/media/pwl-media/PDF-files/White-Papers/2016-06-17_-Bender-Bortolotti_Foreign_Withholding_Taxes_Hyperlinked.pdf?ext=.pdf