I recently received this next question from a blog reader, but I’ve been asked the same thing countless times over the past five years. This is not surprising, since foreign stocks have outperformed Canadian stocks by over 6% each year for the past little while.

Jean-Francois: Why does Vanguard have a 30% weighting to Canadian stocks in its asset allocation ETFs, even though Canadian companies make up only around 3% of the global stock market?

Bender: Thanks for your question, Jean-Francois. In financial lingo, this overweighting is known as a “home bias.” I’m certain other investors have also wondered about the overweight to Canadian stocks in most asset allocation ETFs, as well as in the Canadian Portfolio Manager and Canadian Couch Potato model ETF portfolios.

First of all, no one knows the optimal future mix between Canadian and foreign stocks. I don’t know, nor does Vanguard, BMO, or iShares. Also, a comfortable split for one investor may cause another to abandon their investment plan when things get bumpy, so there’s no one right allocation for everyone.

Let’s review five reasons why overweighting Canadian equities could be a reasonable choice for investors, relative to taking an “agnostic” global market-cap-weighted approach with your portfolio. This should at least leave you with data for making a more informed decision for your own portfolio.

1. Lower Historical Risk

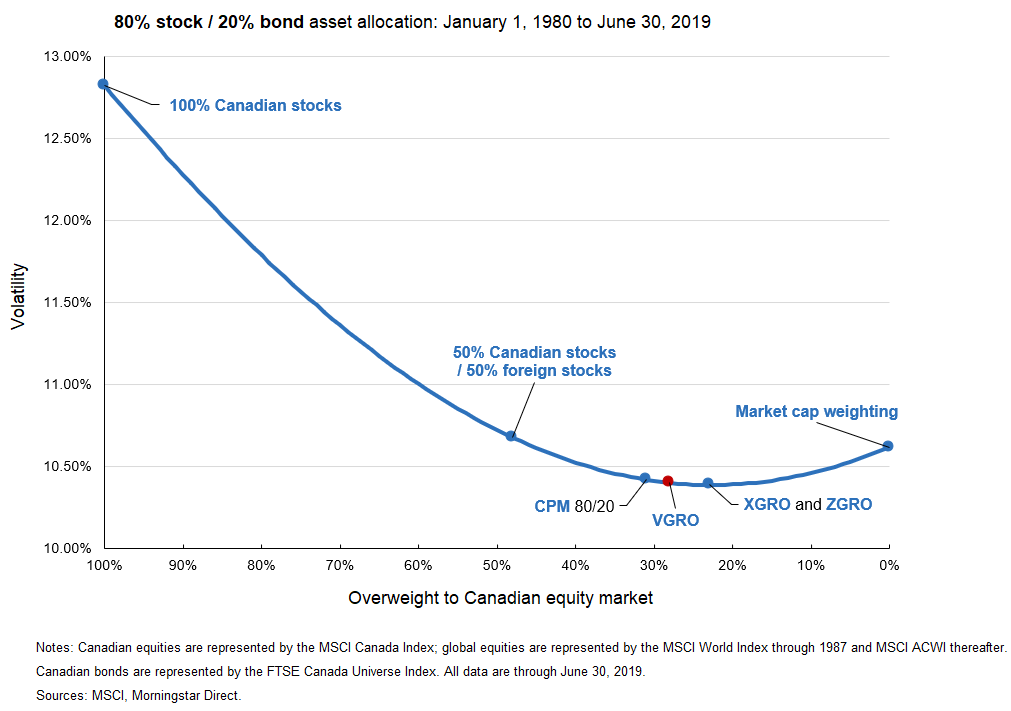

The first reason for overweighting Canadian equities relative to their global market-cap weighting is because this has historically lowered portfolio risk … at least for as far back as I’ve crunched the volatility numbers. For an 80% equity, 20% fixed income asset mix from 1980–June 30, 2019, I found the lowest volatility risk in an equity portfolio holding around 25% Canadian stocks and 75% foreign stocks.

This is similar to how iShares and BMO weight their asset allocation growth ETFs, XGRO and ZGRO, respectively. This minimum-risk portfolio had an average volatility of 10.39% over the measurement period. The average volatility for a global market-cap-weighted growth portfolio (with only around 3% in Canadian stocks), was 10.62%. This portfolio had roughly the same amount of risk as a 50/50 “split of least regret” between Canadian and foreign growth stocks, with an average volatility at 10.68%.

Now, even though a 25% equity allocation to Canadian stocks resulted in the lowest risk for a growth portfolio over this time period, the precise overweighting didn’t seem as critical. Consider the average volatility for a portfolio with a 30% or even a 33% equity allocation to Canadian stocks over the same period. They were all within a few basis points of one another. For example, a 30% equity weighting to Canada (similar to how Vanguard weights VGRO) had an average volatility of 10.40%, or just 0.01% more than a growth portfolio with a 25% equity allocation to Canadian stocks.

Likewise, a 33% equity allocation to Canada (which is similar to our Canadian Couch Potato and Canadian Portfolio Manager model ETF portfolio weightings) increased the average volatility by just three basis points, to around 10.42%. All of these figures were within spitting distance of one another, so they could also be considered “optimal” from a historical risk perspective. They all exhibited much less risk than a growth portfolio invested entirely in Canadian stocks, which boasted a volatility of 12.82%.

Based on these results, I think it’s safe to say that Canadian investors should consider allocating at least half of their equity allocation to foreign equities, and probably more, while at the same time recognizing they can have too much of a good thing.

2. Sector Diversification

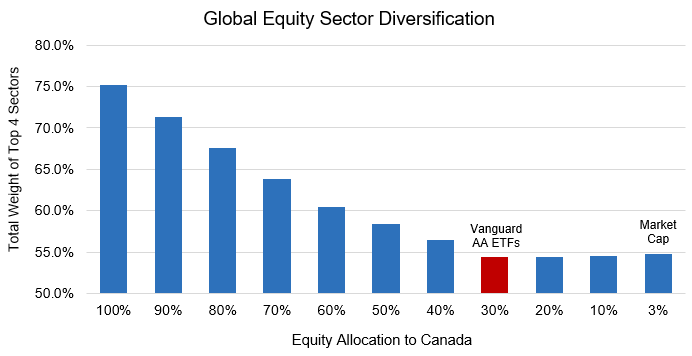

The second reason to consider allocating 30% of your equities to Canadian stocks is because this level of exposure leads to a more diversified sector exposure. The Canadian stock market is overexposed to four sectors: financials, energy, materials, and industrials. These sectors make up around 75% of our domestic stock market. In comparison, the global stock market has a 37.5% weighting to these four sectors, or only half as much exposure.

As we include more foreign stocks into a Canadian-heavy portfolio, the total weight of the top 4 sectors continues to decrease until bottoming out at around 54–55%. This occurs when the split between Canadian and foreign stocks is 30%/70% respectively, i.e., the same split found in Vanguard’s asset allocation ETFs.

Even if we continue to move to a global market-cap-weighted approach by adding more foreign stocks and leaving Canada at around 3%, the grand total of the top 4 sector weights barely budge. This is because the energy and materials sectors just get swapped out for more companies in the information technology and healthcare sectors.

If you have a preference for these hipper tech and drug companies, maybe a global market-cap-weighted portfolio is for you. However, know that you’re still getting decent sector diversification with only a 70% weighting to foreign stocks.

Source: MSCI index fact sheets as of June 28, 2019

3. Single Security Diversification

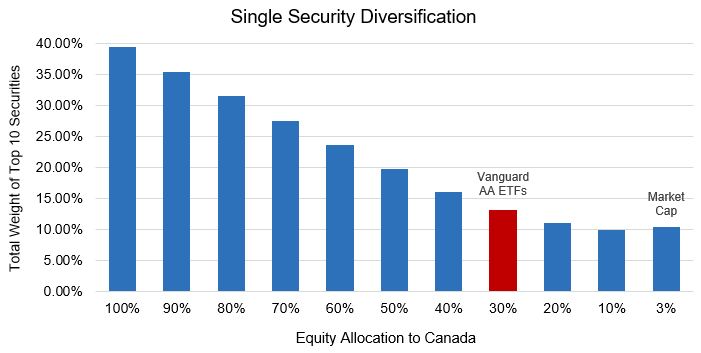

A third reason for allocating about 30% of your equities to Canadian stocks is because the single security risk in your portfolio is largely mitigated at this level. The total weight of the top 10 stocks in Vanguard’s Canadian equity ETF currently accounts for nearly 40% of the fund, with 4 of the big 5 banks accounting for around half of this weight. By splitting your equities into 30% Canadian stocks and 70% foreign stocks, the total weight of the largest 10 stocks in your portfolio drops to around 13%. Sure, you could reduce this figure to about 10% if you were to allocate only 3% to Canadian stocks and 97% to foreign stocks (similar to a global market-cap weighting), but a 30% Canadian equity weighting already provides substantial single security diversification, relative to holding only Canadian stocks.

Source: FTSE Russell index fact sheets as of June 28, 2019

4. Lower Annual Taxes

A fourth reason to have more Canadian equities in your portfolio is because Canadian dividends are extremely tax efficient, relative to the dividend income distributed by foreign equities. In 2018, a top-rate taxpayer in Ontario would have saved over $18 in taxes if they had invested $10,000 in Vanguard’s Canadian equity ETF, rather than in a collection of Vanguard’s foreign equity ETFs. This assumes investing in a non-registered account.

However, the tax savings are not equal across provinces. A top-rate taxpayer in Newfoundland or Labrador would have less incentive to overweight Canada in their portfolio, as the tax benefit was only around $5 last year. On the other hand, a top-rate taxpayer in New Brunswick may have even more reason for a Canadian-heavy portfolio, as their tax savings was around $32 in 2018.

Regardless of your income level or home province, most taxable investors across Canada can justify overweighting their stock portfolio with Canadian stocks (beyond the 3% global market cap).

Unfortunately, if you’re not a taxable investor, and all your investments are in TFSAs and RRSPs, you still have to worry about withholding taxes on your foreign dividends. For Vanguard’s 100% equity ETF (VEQT), the tax drag is around 0.25% each year, or about $25 on a $10,000 investment.

If Vanguard had opted for a global market-cap weighting, with Canada at 3% and foreign equities at 97%, this foreign withholding tax drag would have increased to 0.34% per year, or about 0.09% more than its current set-up. Just remember: The higher the foreign equity allocation in your Vanguard asset allocation ETF, the higher the foreign dividend withholding tax drag in your TFSA and RRSP accounts.

5. Behaviour Benefits

Fifth and finally, we should consider our own behavioural biases – especially recency bias, or our tendency to assume recent performance is going to last forever.

When I started at PWL Capital over a decade ago, investors hated U.S. stocks. I would hear things like, “The U.S. stock market is dead”, and “Why don’t I invest more in Canadian stocks?”

That was behavioural bias at work. Over the decade 1999–2008, Canadian stocks had outperformed U.S. stocks by 9% per year on average. U.S. stocks actually lost almost 4% each year on average in Canadian dollars over that truly “lost decade”. No wonder everyone wanted to dump their “losing” U.S. stocks and load up on our winning Canadian ones.

Many of you probably remember what happened over the next 10 years. U.S. stocks roared back to life. They returned over 14% on average each year, outperforming Canadian stocks by 6.5% annually. Once again, behavioural bias colored the narrative, causing many investors to reverse course to, “Why am I investing so much in Canadians stocks?”

Annualized Performance: Canadian Stocks vs. U.S. Stocks

| Asset Class | Index | 1999-2008 | 2009-2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Stocks | S&P/TSX Composite Index | +5.34% | +7.92% |

| U.S. Stocks | S&P 500 Index | -3.63% | +14.43% |

| Difference | +8.97% | -6.51% |

Source: Morningstar Direct

I’m certainly not trying to predict which stock market will outperform over the next decade. I just want to bring some unbiased perspective to your decision-making. If you want to invest in a global market-cap weighting for reasons that have absolutely nothing to do with recent stock market performance, and you promise to stick with it (even if Canadian stocks significantly outperform foreign stocks), I think that’s fine. But if you’re comfortable with the four other benefits I just described for overweighting Canadian stocks within your stock portfolio, that’s fine too. Can you live with a 30% Canadian, 70% foreign stock allocation, and stick with the simplicity of a one-fund portfolio? That’s all the better for your Canadian home bias.

Justin, I’m still a little unsure. It seems like you don’t think currency risk matters as long as the portfolio is exposed to the US dollar?

You do also say that CAD-hedged ETFs might be a good idea.

So at the end of the day, do you think some level of CAD exposure is good or are you saying 4% CAD is actually fine as long as the other 96% is mostly exposed to USD?

A clarification would be greatly appreciated.

Justin, I realize I’m a little late on the commenting here, but I wanted to let you know that it has tremendously aided my asset allocation decision going forward (that I have been agonizing over for some time now).

I haven’t seen an unbiased, simple to understand explanation of the “home bias” phenomenon as it relates to Canada until stumbling upon this now. Thanks so much! And thanks to the whole team a PWL whos white papers are responsible for much of my current investing knowledge :)

@Matt – I’m so glad you enjoyed the article (and our white papers :)

This is a very interesting article and thank you for writing it.

However, I would counter with:

Point 4 is good and appears to be the only/main reason that makes sense for domestic overweighting, yet it alone does not justify a 27% overweight in my opinion.

Points 1, 2, 3, and 5 are relatively weak and in my mind support global cap weighting. You are essentially favouring active management by making bets on specific countries. Essentially, it is saying that the market is wrong, and that Canada should have a larger chunk of the global market share.

For #1, Canada has had lower historical risk in the past, but it might not in the future. Also, a higher historical Sharpe ratio or annualized return is more important than lower volatility (like Simon’s point).

For #2, you are essentially arguing that a more equal sector weighting would be better than market cap sector weighting, which is another active bet.

#3 provides an argument for global cap weighting. Here you are saying that 30% Canadian and 70% foreign is better than 100% Canadian, not 3% Canadian and 97% foreign.

For #5, straying from market cap weighting increases the odds of making behaviour mistakes, so in my mind it also argues for global cap weighting.

Some arguments I have seen elsewhere include:

Arguments for domestic overweighting:

i) The CAPE is currently highest for the US and near the middle for Canada. Thus, from a valuation perspective, it may make sense to overweight Canada and underweight the US at current levels if you want to make that active bet.

ii) People will generally understand what their domestic companies do better than foreign companies, but this only applies if you are actively picking individual stocks or ETFs.

iii) If you will need to spend the money soon, then having a higher percent in domestic can make sense so that a higher percent is in domestic currency. However, as you mentioned, this is a weak argument with currency hedging and how ETF fees on the TSX should continue approaching those on the NYSE.

iv) It does inspire a sense of nationalism. Obviously, people are happy when their domestic market is outperforming other markets.

Arguments for global cap weighting:

i) It can be shown that maximum diversification is obtained by holding the entire market with cap weighting (from John Bogle’s book). Of course, there are ways to lower volatility. For example, ACWV should have lower volatility than ACWI over the long run, yet I suppose the argument is that ACWI is still more diversified.

ii) Low cost, unbiased cap weighting of entire markets is the original premise/purpose of indexing and passive management (like Jean-Francois’s point).

iii) By overweighting domestic stocks, you are making a multilayered bet on your own country. If your country underperforms, it can affect your employment income and investment income. If your investments are more foreign diversified, then at least your investments shouldn’t theoretically suffer as much.

Again, thank you for your article and if you can reply to this.

@Matthew Morrison – I’m pretty agnostic about this entire home bias discussion. If an investor wants to allocate 50/50 Canada/foreign, I’m fine with that. If they want to allocate based on the current market cap (around 3% Canada / 97% foreign), that’s fine too. If they want to allocate 25% or 30% to Canadian stocks, that’s good with me.

In the end, your own behaviour is going to be the driving force between your success or failure as an investor.

I’m maybe wrong, but I thought one of the reason to overweight canadian equities for a canadian investor was to create a correlation between your portfolio and your country of residence.

It’s a way to keep your Purchasing Power at retirement in the country you will probably retire to.

@Philippe: In the past, some investors felt the need to overweight Canadian equities, mainly because they trade in Canadian dollars and they assumed they would be spending Canadian dollars in retirement. With low-cost currency-hedged equity ETF products now available, I don’t think this argument holds much weight any longer (no pun intended).

Currency risk is one contributor to volatility risk. If you’re a retiree, you’re concerned about volatility in general, and not just currency risk. And foreign currency exposure can decrease volatility, due to a lack of correlation between foreign currencies and foreign securities. Swensen in “Unconventional Success” states that until foreign currency positions constitute more than roughtly one-quarter of portfolio assets, currency exposure serves to reduce overall portfolio risk. Beyond a quarter of portfolio assets, the currency exposure constitutes a source of unwanted risk. That 25% level may be relevant to Americans; perhaps it’s different for Canadians. At market cap weighting, 97% of your portfolio is in foreign currency positions (assumption is no hedging). But volatility is only marginally higher than at the 25-30% Canadian asset allocation levels. OTOH, at market cap weighting, increased volatility due to foreign currency exposure might be masked by the greater diversification benefits of a market cap weighting. About currency hedging, not all risks show up as standard deviation. When stock bear markets occur, the Canadian dollar commonly declines relative to the US dollar; I believe this also holds true for the euro and yen.

As I’m certainly not financially sophisticated, please feel free to correct me.

@Park: I think it’s safe to say that Swensen’s recommendations make sense from a U.S. perspective only.

As Canadians, we have to be careful not to use his U.S. data to make assumptions about our home country portfolio allocations. From a Canadian investor perspective, I would argue that a 50%-97% foreign equity allocation would make more sense, for the reasons outlined above.

I’m on the 30% can equity bandwagon. Good tax advantages, and I live and will retire in Canada spending cad. Now add in the benefits just pointed out in this post and it’s really hard to argue that I would know better than vanguard, ishares, bmo, and of course Justin! As pointed out you need to feel good about your choice and stick with it.

Great post!

@Phil: Thanks! (and for the record, it’s very easy to know more than Justin ;)

This is the best analysis that I’ve seen on why a Canadian should diversify internationally. From what I can see, the major reason for home bias (25-33% Canadian) versus market cap weighting (3%) is tax. That makes sense. In the higher tax brackets, it’s debatable whether a positive expected real return is realistic with foreign dividends. And in a CCPC, tax on foreign dividends only becomes more of an issue. However, if you’re lucky enough to have an income that results in you paying the top Ontario rate, eligible dividends taxed at 39.34% may be a dubious investment. Once you get in the highest brackets, you want to be paying tax as cap gains. That sounds like a good argument for buybacks :-).

Thanks, Justin!

I had an epiphany about this topic while listening to an interview with someone from Vanguard (I think it was on Dan B’s podcast, but am not sure my memory is correct here), which was that since Canada’s economy is so heavy in commodities and natural resources, over-weighting Canadian equity actually provides a broader exposure to different/uncorrelated asset types – even though it seems to be concentrating risk on a relatively small portion of the cap-weighted global economy.

This is the case for Australia’s economy too, apparently. To me, this helped to explain why volatility was reduced by an increased concentration of Canadian equities – it provided greater sector diversity. Over-weighting wouldn’t work with *any* country… just those that don’t correlate well with most of the rest of the global economy.

@Phil: That could be one of the reasons for the reduction in volatility of a 30% Canadian equity allocation (relative to a market cap weighted 3%). A significant portion of global equities are made up of U.S. equities (and therefore, U.S. dollars). The U.S. dollar has historically had a negative correlation to Canadian equities (which have a significant exposure to energy and commodities companies).

Hello Justin!

I hope you are well!

First I would like to tell you how grateful I am that you took the time to prepare a thougrough analysis of the matter although I was too lazy to record the question for you. Really, what you are doing for the investment community and retail investors is amazing and invaluable. I am not sure you and I can realise how many people you have and are still helping with all your posts. This certainly defines you as person with incredible values, that walk the talk and I respect that to the highest level possible.

That being said, much like Simon mentioned in a comment above, I feel like these facts and details you have provided are reasons to justify the overweight, like better tax efficiency, company risks and so on. The reason I am still not comfortable with a 30% allocation when market cap is around 3-5% for Canada, is that this sounds like active management that is taking a bet on a region or a country by overweighting it. The whole point of indexing and passive investment I believe is about having a neutral view of the market and to allocate ressources where efficient as determined by the market and accepting market returns. Portfolio allocation of a market cap index is not based on tax efficiency, company risks, or anything else.

There is something scary for me in investing 30% of your investment on a small and undiversified economy like Canada. There are certainly reasons as to why the market values Google or Microsoft (tech companies) higher than Shell or Petro-Canada (Natural ressources) for example. With a 30% allocation, you are actually taking a bet against tech companies because you underweight it and a bet in favor of natural ressources and this is against passive investment, which is accepting neutral market returns minus costs. This is not what I see in Vanguard’s or Ishares or any other asset allocation market cap product in fact. There is not ONE single product that is actually a fully indexed market cap globally diversified across size, region and low costs.

I am pretty sure that if you ask an active manager as to why he allocates his portfolio the way he does, he will justify it by trying to maximise risk/reward ratio and minimise taxes, etc., but as you know, it rarely works according to data.

I feel important to mention that I do not want more international stocks for recent returns reasons, but rather because I am a purist and the index methodology should be neutral and allocate ressources in the market’s proportion. Anything else is active managment using indexes in my opinion. Am I correct or do you feel I exagerate the importance of pure passive investment / indexing ?

Once again, thank you Justin for your work and insight, I do appreciate it a lot and look foward to future conversations with you. Take care and keep up the amazing work, it is always a pleasure to read you :)

Jean-François

Hi Jean-Francois L-D: Thank you for your kind words – I really appreciate the feedback :)

As you could tell by the tone of the article, I don’t have a strong opinion with regards to home bias. This is due to the behavioural issues I have witnessed countless investors struggle with during times when Canadian stocks outperformed foreign stocks – many investors reading this blog started investing after this period, so they can’t truly know how they would react to this particular situation.

If an investor prefers to hold 50% in Canadian stocks and 50% in foreign stocks, I think that’s fine. Likewise, if you prefer a true passive approach of holding about 3% in Canadian stocks and 97% in foreign stocks, I think that’s great too. At PWL, we’ve chosen a target of around 1/3 in Canadian stocks, which we feel is appropriate, given all of the other benefits of holding Canadian stocks. Vanguard chose 30%, while iShares and BMO chose 25%. The main point is to choose something you are comfortable with and stick with it over the long term.

Thank you Justin for your quick and insightful answer!

Although I did show an opinion on the subject, I do understand that the differences between the two methodology yield practically the same results.

You are also correct that I did not go through an experience such as seeing the Canadian stock market outperforming and holding only 3% of it! I also understand that these products are generic and developped for a most investors and suitable in a taxable environement too, so all in all, it does make sense that the producst have been developped that way.

At this point, as you said, it is a personal preference, but both should do just fine!

Thanks again Justin :)

Best regards,

JFLD

An interesting perspective on home bias. You mention that the overweight positions on Canadian equities can reduce volatility, but can’t it also increase volatility? During the Great Recession, both the US and Canadian markets lost about 50% of their value, but due to the depreciating Canadian dollar, US equities in Canadian equivalent only lost about 36%. Just a thought.

@GregJP: Correct – too much home bias would be expected to increase the volatility of a portfolio. You can see this in the first graph above, where a 100% Canadian equity allocation is much more volatile than any other mixes.

I’ve allocated 20% of my equities portfolio to Canadian stocks (VCN) and this makes me feel a lot better about that decision. It looks like 20-30% seems to be the appropriate allocation, and I am choosing to overweight but still be at the lower end given some of the inherent flaws with the Canadian equities markets. Please do let me know if there is any compelling reason to (long term) switch towards a 30-33% Canadian allocation – I always considered doing so closer to retirement time due to currency risk but I am about 40 years from retirement.

PS: I am surprised you never mentioned currency risk since that is what I have always heard as a major consideration, but I see in the comments you do not think this is an issue.

@Brandon: A 20% Canadian equity allocation seems reasonable, based on the discussion above (I don’t see any reason to switch to a 30% or 33% weighting if you’re comfortable with 20%).

Currency risk is something investors can always mitigate by using currency-hedged foreign equity ETFs (if they felt strongly about this risk). As investors approach retirement, they would generally be reducing their allocation to foreign equities anyway (and subsequently, reducing their currency risk as they decrease their allocation to foreign equities).

Hi Justin.

I’ve got a question regarding wealth simple. I put my mother (58yo) in a balanced 50/50 portfolio. up until 2 weeks ago the equities portion seemed like what you would expect as far as splits between canadian, US, developed intn’l, and emerging. 15% US, 12.5% CAD, 7.5 Developed international, 5% Emerg, 10% real estate. 2 weeks ago it got a re-balance. weighting emerging markets at 15%. Same as international and US. CAD going to 5%. I picked this fund as it is a passive hands off portfolio. This re-balance has me questioning weather or not wealth simple knows what passive means. They’re trying to speculate that Emerging markets are going to out perform Canada. This time they could be right (who knows), but i’m not willing to bet that over the next 25 years they’re going to guess right often enough to even match the market, let alone beat it. Do I get her out of this and put the money into VBAL and reinvest the dividends myself once a quarter (which I do for my own accounts)

@Morgan McGrath: I heard about Wealthsimple’s recent portfolio changes. Just when I thought their portfolios looked pretty decent (low-cost, broad-market ETFs), they changed them (I guess it’s very difficult for investment companies to just leave well enough alone).

If this wasn’t what you signed up for, you could consider one of the asset allocation ETFs (like VCNS or VBAL, or a combo of the two) with a more consistent methodology and strategy.

I’d love to see a slightly more detailed critique of what they’re doing. This would seem a good time to reassess whether your model portfolios or Wealthsimple is going to be better over the long term.

@Andrew: There’s no way to know which portfolios will outperform going forward, so no back-test or critique will assist you in determining this. You should first decide which investment philosophy you want to follow, and then stick with it.

Both the Vanguard AA ETFs and the CPM model ETF portfolios use a very passive index approach, so should have similar returns going forward. Wealthsimple appears to have switched to a mix of these strategies + low-volatility ETFs, so their returns will differ (either better or worst) from the other more passive strategies.

Hi. Thank you for the article

Isn’t lower volatility a bad thing for someone in accumulation phase (good for someone in distribution phase).

I think someone that is working and earlier in his career should pray for higher volatility because this person is DCA regularly so that person can buy at lower price. Obviously I think the opposite is true for someone in retirement.

If so reason 1 can be either a positive or a negative depending on the situation.

@Math: From a behavioural perspective, I think most investors would prefer a smoother ride with their investments, even during the accumulation phase.

From a rational perspective, someone saving earlier in their career would prefer to see a very long, drawn out market downturn (which doesn’t impact their employment earnings), and then a market recovery right before retirement (but I wouldn’t bank on this scenario).

Justin, I commend you for diving into this topic but I must admit I am a little disappointed with the analysis. It seems like you are characterizing the 30% Canadian allocation as “good enough” vs. the market cap approach especially on your points of sector and company diversification. Taxes are a consideration but we shouldn’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog where asset allocation, diversification and low costs are key. As for the analysis relative to volatility, I’d love to see the analysis more fleshed out considering returns and volatility under a Sharpe/Sortino lens vs. just pure volatility.

Principally I am all for global diversification at low cost and am against home bias. If Vanguard, iShares or BMO came out with an all in one ETF that actually gave Canada a proper cap weight of 3-5%, I would definitely consider it instead of VTI/VXUS/XAW.TO today that is used for equities in my portfolio.

@Simon: If you’re comfortable with a 3% Canadian equity allocation, I don’t see any issue with this type of portfolio either. The discussion was meant to point out a number of benefits of overweighting Canada in a portfolio, relative to the global market cap (these benefits should be a consideration for investors, and not just simply ignored).

Great post! One other consideration I make is the currency. I like to keep around half of my portfolio in securities exposed to the Canadian dollar. That’s between Canadian equities and Canadian (and CAD-hedged foreign) bonds. Whether that can be backed up by evidence or not, it provides me comfort and helps control my emotions when I see bigger CAD fluctuations from time to time.

@Bjorn: Thanks! I’m less concerned about the currency fluctuations over the long term. Historically, the exposure to the U.S. dollar has resulted in substantial volatility reduction (relative to an all-Canadian equity portfolio). However, I think your comfort level with your investment strategy should outweigh any historical back-test, so I’m glad to hear you recognize the benefits of controlling your emotions :)