In past posts, when I’ve mentioned making corporate investments to better feather your company nest, I’ve suggested taking a relatively conservative approach. Companies and individuals alike can get burned by flying too high in pursuit of hot stock tips. That said, a modest allocation to the stock market can make sense, lest your nest eggs ultimately yield little more than a goose egg’s worth of returns.

If you do choose to invest some of your corporate investments in equities, some of the returns will take the form of capital gains, so let’s brush up on the tax implications of earning these within a corporation.

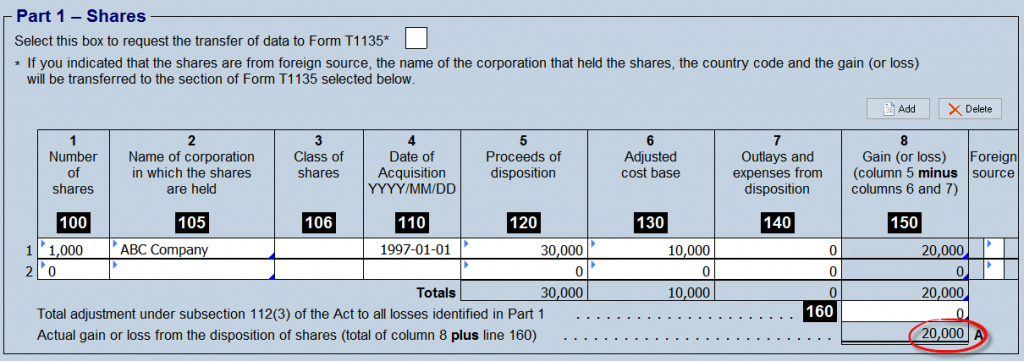

For our example, we’ll assume an Ontario business owner purchases $10,000 in stocks in their corporate account in 1997. Fortune smiles on the investment and, by 2016, it’s worth $30,000. (Caveat: Remember stocks can just as easily underperform, especially across a few years, so it’s usually best to temper riskier equity investments with some safer holdings as well.)

To lock in the ample returns, the business owner sells the holdings, realizing a $20,000 capital gain ($30,000 – $10,000). At tax time, they enter the purchase and sale details on Schedule 6 of their 2016 corporate tax return.

Source: 2016 Corporate Taxprep, Schedule 6 (Summary of Dispositions of Capital Property)

Two sides of the same coin

For corporations and individuals alike, only half of the realized capital gain is taxable as income, while the other half is tax-free. So, for reporting purposes, what happens to that $10,000 taxable portion, and where does the non-taxable half go?

First, federal taxes of 38.67% are levied on the taxable portion of the capital gain (with 30.67% refundable and 8% non-refundable), followed by non-refundable provincial or territorial taxes. In Ontario, this results in 50.17% of total investment taxes payable (38.67% + 11.5% in Ontario).

Tax integration for the taxable portion of capital gains also works the same as for interest income. Both the after-tax corporate income and the refundable taxes are available to distribute to shareholders. Once these are distributed, they are taxable in the shareholder’s hands (I’ve included the same example below from Corporate Taxation: Tax Integration of Canadian Interest Income).

Corporate Taxation and Tax Integration of the Taxable Portion of Capital Gains

| General Formula | Amount | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Taxable portion of capital gain | $10,000 | $20,000 × 50% |

| Deduct: Part I tax – non-refundable | ($800) | $10,000 × 8% |

| Deduct: Part I tax – refundable | ($3,067) | $10,000 × 30.67% |

| Deduct: Provincial or territorial tax – non-refundable | ($1,150) | $10,000 × 11.5% (Ontario) |

| Equals: After-tax corporate income | $4,983 | $10,000 - $5,017 |

| Add-back: Refundable taxes | $3,067 | $10,000 × 30.67% |

| Equals: Amount available to distribute as a taxable dividend | $8,050 | $4,983 + $3,067 |

| Deduct: Personal tax payable | ($3,647) | $8,050 × 45.30% |

| Equals: After-tax cash | $4,403 | $8,050 - $3,647 |

It’s not half bad

That’s not the entire story though. There’s still the matter of the non-taxable half of the capital gain. If this weren’t separately accounted for, it would end up taxed as an ineligible dividend when it was eventually distributed to the business owner (which doesn’t seem fair, as individual investors pay no tax on this part of the gain).

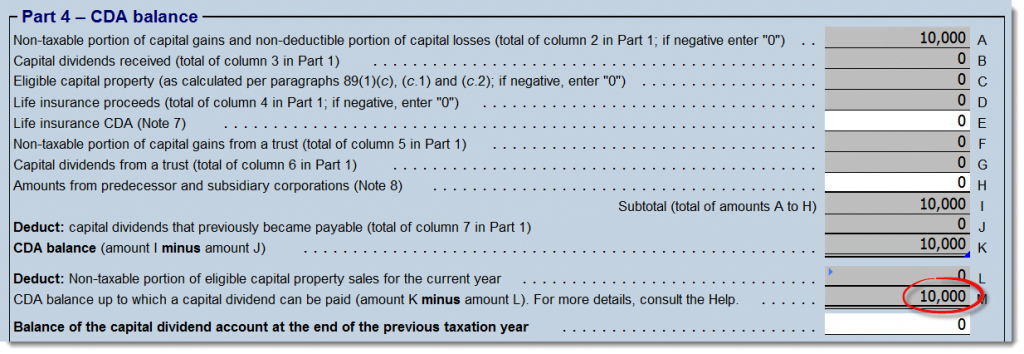

Thankfully, capital dividends come to our rescue. As it turns out, the government allows the non-taxable portion of the capital gain to be distributed tax-free to shareholders. The balance of tax-free amounts available for distribution are tracked in a notional account cleverly entitled the capital dividend account (CDA). If there is a positive balance in the CDA, these tax-free capital dividends can be paid to shareholders.

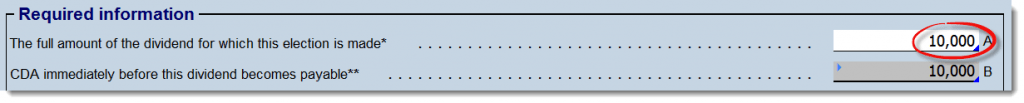

As you might expect when the phrase “tax-free” is involved, the Canada Revenue Agency is very strict on the steps required to distribute capital dividends. For the dividend to be tax-free, the company must file an election using Form T2054 – Election for a Capital Dividend Under Subsection 83(2), on or before the earlier of the day that the dividend is paid or becomes payable. A certified copy of the Director’s resolution authorizing the election, and a calculation showing the amount of the corporation’s CDA balance must also be included in the filing. Any errors can result in significant tax penalties.

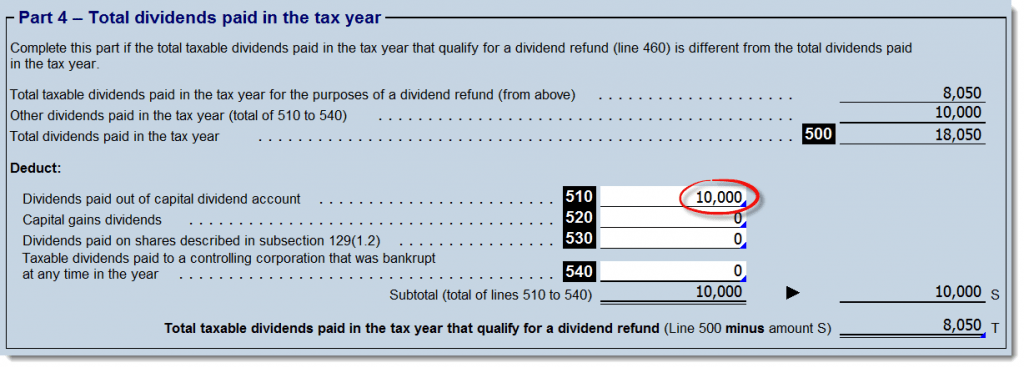

Once the dividends have been paid from the capital dividend account, they are included on line 510 of Schedule 3.

Source: 2016 Corporate Taxprep – Form T2054 – Election for a Capital Dividend Under Subsection 83(2)

Source: 2016 Corporate Taxprep – Schedule 89 – Request for Capital Dividend Account Balance Verification

Source: 2016 Corporate Taxprep – Schedule 3 – Dividends Received, Taxable Dividends Paid, and Part IV Tax Calculations

If you’ve been following my corporate taxation series, the only new concept from this blog post is the use of the capital dividend account, which makes this post a relative recess for you. Next up, we’ll get back in the classroom to discuss a corporate capital gains tax strategy called Tax Gain Harvesting.

Great article! Keep posting content like this!

So is there any benefit on creating a c corporation to invest your money instead on doing it in my individual portfolio?

@Emilio: Generally, there’s not expected to be a benefit of investing within a corporation (after costs), unless you’re earning active business income and saving a portion of it in the corp.