During periods when global stocks have been outperforming Canadian stocks, I receive a growing number of questions asking why my model ETF portfolios are skewed so heavily towards Canadian stocks (as one might imagine, I receive the opposite feedback when Canadian stocks are outperforming global stocks). The argument usually goes something like this: Canadian stocks make up just over 3% of the global equity markets – shouldn’t Canadian investors simply hold a 3% equity allocation to Canadian stocks?

I’ll let you all in on a dirty little secret: no one knows the optimal amount of Canadian stocks that an investor should hold. Not me, not the talking heads on BNN, not anyone. All we can hope to do as mere mortal investors is to make a reasonable guess that we are comfortable with, and stick with it over the long term.

As mentioned, Canadian stocks make up just slightly more than 3% of the global equity markets. But in my model ETF portfolios, I overweight Canadian stocks by about 30% (resulting in a 33% allocation, or 1/3 equity weighting towards Canadian stocks). There are a number of good reasons for doing so, which I’ll cover in a series of blog posts.

Reason #1: The minimum risk portfolio has historically overweighted Canadian stocks by about 30% (relative to a market capitalization-weighted index portfolio).

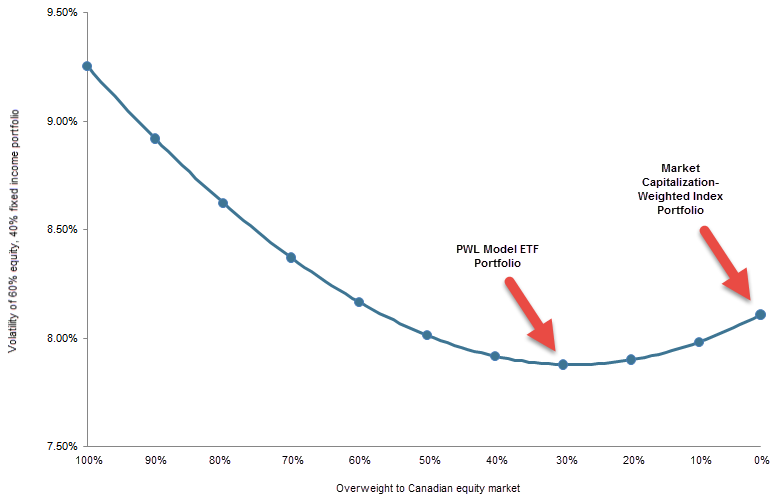

If we assume that the future expected returns for Canadian stocks are similar to global stocks, rational investors would prefer a blend that results in the least amount of portfolio risk. In the graph below, I’ve calculated the historical volatility for various balanced portfolios between 1988 and 2015 (with a 60% allocation to stocks and a 40% allocation to bonds). Each portfolio along the curve overweights Canadian stocks by varying amounts.

Minimum Risk Portfolio: January 1988 to December 2015

Notes: Canadian equities are represented by the MSCI Canada Index; global equities are represented by the MSCI ACWI Index. Canadian bonds are represented by the FTSE TMX Canada Universe Bond Index.

Sources: MSCI Indices, Dimensional Returns 2.0

To the far left of the graph, you’ll find a balanced portfolio that invests 100% of its equity component in Canadian stocks (you may also notice that it has the highest risk, or volatility, of all the portfolios). Most investors realize that this is an extreme position, and that significant diversification benefits can be achieved by investing some of their equities into global stocks.

As we move further along the curve to the right, we find that the portfolio risk bottoms out at around a 30% overweight to Canadian stocks (a similar mix to my PWL model ETF portfolios). As we continue to the far right of the curve, we reach the market capitalization-weighted index portfolio. Indexing purists will often argue that this is the most optimal portfolio, as it is the most diversified and requires no active decision-making. Contrary to what they believe, this portfolio has historically been more volatile than a portfolio that overweight Canadian stocks by 30%, or even 50%.

In their 2014 research paper that followed a similar methodology as the analysis above, Vanguard Canada was quick to point out that their analysis was backward-looking and particularly dependent on the time period examined. The specific asset allocation (the mix between stocks, bonds and other asset classes) also affected the historical results. Without knowing what the future holds, a reasonable starting point would arguably be between a 20% and 40% overweight to Canadian stocks.

In my next blog post, I’ll look at a number of other reasons that it may make sense for a Canadian investor to overweight Canadian stocks within the equity component of their portfolio.

Thanks, Justin. Appreciate this. Obviously, I wasn’t the only one asking about this :) Looking forward to the next one.

@Carsten: You certainly were not the only one – I lost track of how many times I received this question in 2015 ;)

The next one has now been posted! http://www.canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/ask-bender-canadian-stocks-vs-global-stocks-part-ii/

Hi Justin – I really appreciate your well-prepared posts – regarding global equity – I read somewhere in the past year or so – I’m not able to track down where I read it – that XEF is more advantageous than other international equity etf’s in non-registered accounts – because more of it’s total return comes from capital gains – with a smaller percentage of the total return coming from dividends – vs other international equity etf’s where capital gains tend to form a smaller percentage of the total return – and thus XEF is more tax efficient in non-registered accounts – do you have any insight into whether what I’ve just outlined is in fact the case – thank-you

@James R: XEF is more tax-efficient than international “wrap ETFs” (like VDU) in non-registered accounts as it holds the underlying stocks directly (which avoids a layer of foreign withholding taxes). You likely read either one of my recent blog posts on the subject: http://www.canadianportfoliomanagerblog.com/foreign-withholding-taxes-in-international-equity-etfs-revisited/ or my recent updated white paper on the subject: https://www.pwlcapital.com/pwl/media/pwl-media/PDF-files/White-Papers/2016-06-17_-Bender-Bortolotti_Foreign_Withholding_Taxes_Hyperlinked.pdf?ext=.pdf

This is all nice but again, if the only reason is past returns … then we all know what they’re worth ! There’s also a taxation advantage. If we were to imagine a total return of 8% made of 6% cap gains and 2% dividends, the Canadian stocks would perform marginally better due to taxation. I’m sure there are other reasons but personally, since my life, employment income and general quality of life is heavily dependent on Canada’s economy, I prefer to diversify and allocate 10% of my equities portfolio to Canada and 90% to an All-World (ex-Canada) ETF.

We also have to consider that Country-based allocation has its limit in a global economy. For example, Dream Global REIT which is officially part of Canadian equities has 0 income and real estate properties in Canada. The same argument can be made for US-based companies like GE, Apple, Ford, etc. So this is just a few examples showing how managing diversification by countries has its limits.

@Linda Rocco: If you’re comfortable with a 7% overweight to Canadian stocks, I don’t see any issue with this in theory. In practice, it can prove to be very difficult during periods when Canadian stocks outperform (my next blog post will touch on this behavioural issue).

once again this is very informative. thanks Justin!

In your example, there is a 60% allocation to stocks and 40% allocation to bonds.

1) Would the volatility risk curve be the same if I am 80% stocks and 20% bonds? Would the point of minimum volatility be at another percentage?

2) Is your volatility curve explained in part by currency exchange? by having more Canadian equities overweight, you have less currency fluctuation?

@D: In Vanguard’s paper, “Global equities: Balancing home bias and diversification – A Canadian investor’s perspective,” they ran a similar analysis for various asset allocations – but they all seem to be around the 30% mark (see graph on page 6): https://www.vanguardcanada.ca/documents/global-equities-tlor.pdf

Your second question is a good one. In order to determine this, I would need to sub in the returns of a global equity index (the MSCI ACWI Index) denominated in local currencies (which would be arguably similar to a currency-hedged ETF), and see if the main volatility reduction benefits are coming from the equity diversification or the currency diversification. Unfortunately, the current analysis took me almost an entire evening, so I’ll need to look at this later.

@D: I quickly ran the analysis (using increments of 10% so it didn’t take me as long as the first one) – the graph looks similar to the one I posted. The 30% overweight to Canadian equities is still the portfolio with the least amount of risk, at 8.50%. This compares to a volatility of 7.88% for the balanced portfolio with a 30% overweight to Canadian stocks that had exposure to the underlying currencies. It is also lower than the 100% Canadian-equity balanced portfolio, which had a volatility of 9.26%.

So to answer your second question, about 55% of the decrease in volatility is coming from the equity diversification, and about 45% of the volatility reduction is coming from the currency diversification.

Here’s something of interest. The Canadian stock market for 2016 is the third best in the world as of September 1st. Not always but at times it’s better than most. Who would have guessed a year or 4 ago. The magic wand of determining where to place your money is never easy. Justin and Dan B. help many of us with well written and timely articles. Thanks for the posts.

@John lubber: You’re very welcome – thank you for reading them! I was a little late on this post…since the Canadian stock market has been outperforming global stocks year-to-date, less questions have been rolling in about my bloated Canadian equity allocation ;)